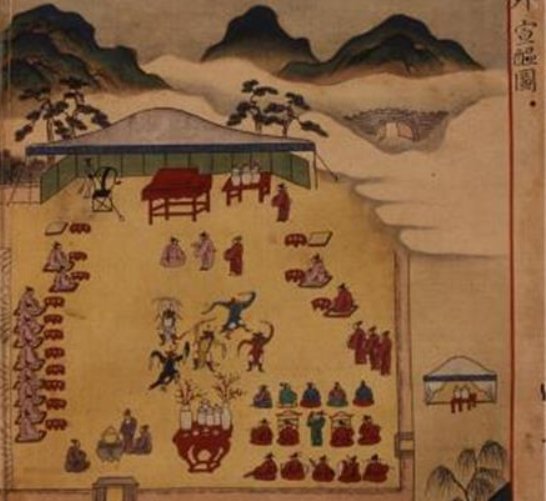

The furniture illustrations in this chapter come from the collections of selected Korean museums. Most of the pieces date from the late Joseon dynasty, specifically from the late 18th and 19th centuries. The study is relatively complex, given the limited amount of information available on the subject. Our deductions are based on the analysis of photographs and information gathered about the Joseon dynasty.

JOSEON & THE KOREAN EMPIRE FURNITURE.

Joseon was a dynasty founded in 1392 by King Taejo Lee Seong-gye, and the first country was named Goryeo and its capital was Gaeseong. Afterwards, the name of the country was changed to Joseon in 1394, and the capital was moved to Hanyang (presently Seoul) in 1398, where it remained as the capital for about 500 years. A total of 26 kings ruled for about 505 years and ran the country with a policy of pro-Confucianism and suppression of Buddhism. In 1897, the name of the country was changed to Daehan Empire and it was declared an imperial state. A total of two emperors ruled for 13 years, ending in 1910 with the reign of Gyeongsul.

Furniture made for the royal court often had more elaborate details and higher-quality materials compared to those used by commoners. The royal pieces might include more intricate inlay work, fine lacquer finishes, and detailed carvings.

Artisans used mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, and other materials to create elaborate patterns and images. These inlays often depicted traditional Korean motifs such as flora and fauna, geometric patterns, and symbolic imagery like dragons and phoenixes, which represented power and prosperity.

The application of lacquer was another key characteristic of royal furniture. Lacquer enhanced the aesthetic appeal with a glossy finish. Royal pieces often had multiple layers of lacquer, which were meticulously polished to achieve a deep, lustrous shine.

Royal furniture also featured ornate carvings. These carvings could be found on various parts of the furniture, including legs, edges, and panels. Common motifs included dragons, phoenixes, clouds, and other auspicious symbols. The carvings were not only decorative but also conveyed the power and status of the royal family.

Symbolism played a significant role in the design of royal furniture. Dragons, for instance, symbolized the king’s authority and power, while phoenixes represented the queen. Cranes symbolized longevity, and peonies represented wealth and honor. These symbols were carefully chosen to reflect the virtues and aspirations of the royal household.

The craftsmanship of royal furniture was of the highest caliber. Skilled artisans spent significant time and effort on each piece, ensuring that every detail was perfect. The artisans’ expertise was evident in the precise joinery, flawless inlays, and harmonious proportions of the furniture.

It is also important to highlight that The Joseon Dynasty imported Chinese furniture, especially during periods of close diplomatic relations with the Ming Dynasty. However, due to the influence of Neo-Confucianism, the Joseon Dynasty looked down on the culture of the Qing Dynasty, and cultural exchanges decreased significantly compared to those during the Ming Dynasty.

Cabinets, tables, and chairs were among the types of furniture imported from China. These pieces often featured more elaborate carvings and inlays compared to traditional Korean furniture.

Imported furniture was often seen in royal palaces and among the elite, symbolizing cultural refinement and prestige.

Specific types of furniture were made exclusively for the royal court, including thrones, large storage chests, and special ceremonial tables.

THE KING’S QUARTER FURNITURE.

The Phoenix Throne (Korean: 어좌; eojwa) is the term used to identify the throne of the hereditary monarchs of Korea. Located at the center between the convenience hall and audience hall in the royal palace, the royal throne was a seat occupied by the king when he accepted an official’s felicitations, held court assembly and handled state affairs. It was also called “Okjwa” (jade seat) or “Bojwa” (treasure seat).

The royal throne was constructed of wood and painted red, a color used exclusively by royal court. It was decorated on all surfaces with dragons flying amidst gold clouds. The corners were decorated with carved yellow dragons heads

The phoenix motif symbolizes the king’s supreme authority. It has a long association with Korean royalty.

The throne is a chair on which a king or emperor sits, also referred to as a jade or treasured throne. Unlike the thrones of the Joseon Dynasty, which were red, the thrones of the Korean Empire (1897 – 1910) were painted yellow to symbolize the emperor. The entire structure is adorned with a five-clawed cloud dragon pattern, and gold dragon heads are placed on each of the upper corners.

Note: The Korean Empire, officially the Empire of Korea or Imperial Korea, was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by King Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire stood until Japan’s annexation of Korea in August 1910.

H. 55cm, W. 72.5cm, length of the stick: 190cm. Collection: Gyeonggi provincial Museum.

“Juchilgyoui” refers to a chair painted with red pigment (朱漆) and was used in pairs with a footrest called “gakdap”. This furniture piece was exclusively used during ceremonial ceremonies by the royal family. The legs and handles are adorned with a cloud dragon pattern in gold at the base, and a lotus pattern is carved into the center of the backrest. A fern-shaped pattern is carved in the lower part, while water, the sun, and clouds are depicted in relief on the upper part.

Collection: National Palace Museum of Korea.

The 53rd My Art Auction, Seoul, Korea.. Date: September 12, 2024.

This palanquin is decorated with lotus flowers and phoenixes on the roof, with a dragon carved in openwork just below it. Various plants are designed beneath that, including grapes and longevity patterns, while the lowest part features an ansang pattern. It is believed that this palanquin was used by royal concubines and princesses, known as Deung or Deungcha. Deung were used by royal women when entering or exiting the palace, and it was also the type of palanquin used in 1847 when King Heonjong welcomed Lady Gyeongbin Kim (慶嬪 金氏, 1831-1907) as a concubine. This palanquin is in excellent condition, with even the flower-patterned stones inside well preserved.

[Reference] Je Song-hee, “A Study on the Palanquins of the Joseon Royal Family,” Korean Culture, 70, Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, Seoul National University, 2015.

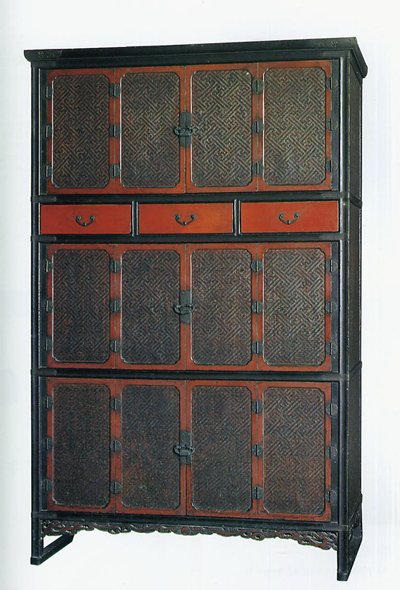

Large lacquered book chest made of pine and ginkgo wood. H. 176 cm, W. 106 cm, D. 51.5 cm. Collection: Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

This book chest, made during the Joseon dynasty, was used in the royal palace. It is composed of two large hinged doors and one shelf inside. The pillars of the chest are in the form of grooved metal, a style mainly seen in the 16th and 17th centuries. Four small plates were created above and below the door compartment, decorated with black lacquer engraved with “Yeouidu” patterns. The door front decoration is divided into two parts, with the lower section featuring Yeouidu motifs. The upper section is divided into twelve compartments, with dragons centered around Yeouidu patterns. The carved dragon motifs are painted with vermilion over a panel painted in black lacquer to provide contrast. Black and red lacquer colors were mainly used by the royal court of the time. The legs’ corners are engraved with openwork arabesque patterns on the bottom front and sides.

Collection: National Palace Museum, Seoul.

H. 27cm, W. 36cm, D. 23cm. Collection of the National Museum of Korea.

There are trace of vermillion lacquer showing the characteristics of a furniture given by the Royal family.

THE QUEEN’S QUARTER FURNITURE.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Palace Museum of Korea.

H. 130cm, W. 70cm, D. 35cm.

Collection: National Palace Museum, Seoul, Korea.

Collection: Sookmyung women’s University, Seoul.

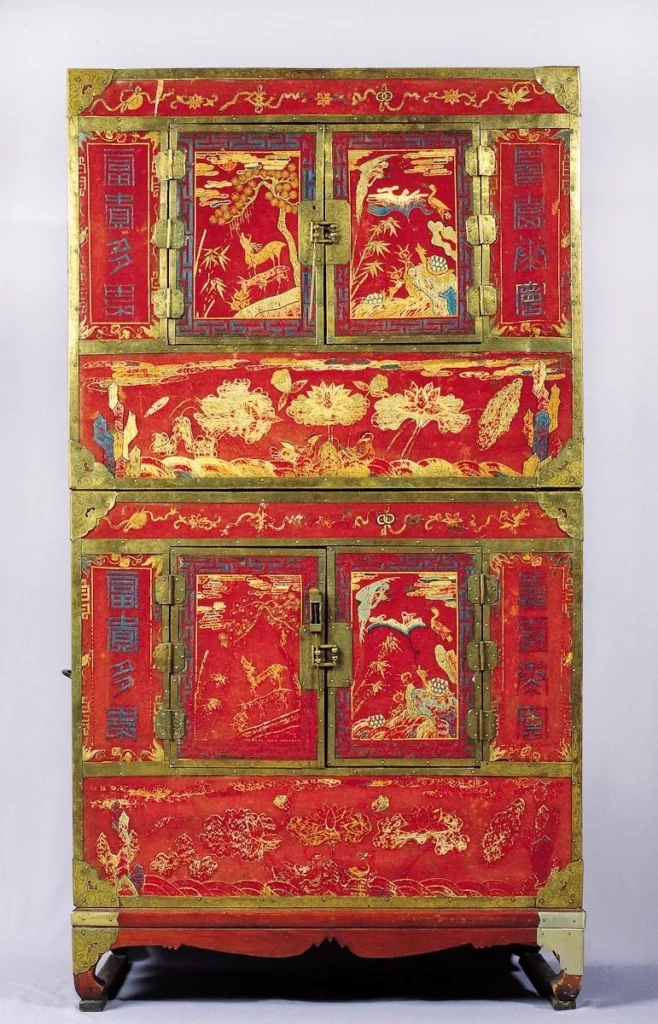

This lacquered cabinet is an early form of a Nong. It was covered with vermillion lacquer and appears to have been used in the royal palace. The border of the doors was painted black.

It is believed to have been produced around the 18th to 19th centuries.

This embroidered chest is said to have been produced for the garye (wedding) of queen Sunwon, who was the wife of Sunjo, the 23rd king of the Joseon dynasty (29 July 1790 – 13 December 1834). The ten traditional symbols of longevity were embroidered on the door and on the lower part of the door, lotus flower and mandarin duck designs were embroidered so as to wish for the couple to be happy and bear many children.

Collection: Sookmyung Women’s University Museum, Seoul. Korea.

This relic is a two-story Nong crafted from paulownia wood, with its front adorned in red brushed fabric featuring various embroidered patterns. It is believed to date back to late 18th or early 19th centuries. One theory suggests it was created during the wedding ceremony of Queen Sunwon, the consort of the 23rd King of Joseon, Sunjo, which occurred in 1802.

The chest’s design represents a typical style of Nong during the Joseon Dynasty. It consists of two boxes of the same standard joined together at the top and bottom on a bat-shaped pedestal, with the frame constructed from paulownia wood.

The corner pieces on both the front and back sides of the chest, the fittings on the sides of the door, the doorknob, and the lock are crafted from brass, and the edges of the entire piece are also embellished with brass. The brass is intricately engraved with a floral pattern. The overall dimensions of the frame are 77cm wide and 138.5cm high. The embroidery is exclusively attached to the front of the chest.

The embroidery patterns were arranged with consistent themes and compositions on both the upper and lower levels. The door panels on the left and right are adorned with Ajamun (亞字文) motifs in navy blue, encircling the borders, while the Ten Longevity Symbols (十長生紋) are embroidered on the inner sections. The right door features embroidery depicting cranes, clouds, bamboo, turtles, the herb of immortality, rocks, and water waves, whereas the left door showcases embroidery depicting the sun, clouds, pine trees, bamboo, deer, and the herb of immortality.

The space on the left and right sides of the door was divided by a rectangular line. On the left, the auspicious symbol of ‘riches’ was embroidered with indigo thread, while on the right, ‘壽福康寧’ (longevity, blessings, health, peace) was embroidered. Outside the border, a pattern combining gourds and auspicious characters was embroidered.

The embroidery at the bottom follows a lotus pattern theme. Clouds adorn the top, rocks flank both sides, and lotus flowers and leaves blooming on waves are prominently depicted in the center. Two mandarin ducks are placed beneath the lotus flowers.

The Ten Longevity Patterns and Lucky Sign Patterns were among the most frequently used motifs in crafts during the Joseon Dynasty. They bear auspicious meanings, symbolizing wishes for longevity, good fortune, and prosperity in life.

VARIOUS PIECES.

This furniture did not necessarily belong to the Korean royal court, but it does have all the characteristics of such pieces.

Auction: Christie’s March 28, 2006.

Rectangular with top corner brackets, central pair of doors opening to the inner cabinet and bracket feet, carved with small rectangular floral panels separated by raised borders

30 3/8 x 27 1/8 x 15¼in. (77.3 x 69 x 38.7cm.)

Auction: Christie’s September 17, 2009.

With circular top raised on high cabriole legs connected by two slats and an apron of reticulated knots and applied with red lacquer, details incised; inscribed on underside in hangul with date 4th year of the reign of Chinese emperor Tongzhi (1868) and with the name of the maker, a Juji Junjo of Hakpong-ri (?)

35 3/8in. (90cm) diameter; 18½in. (47cm) high

Photos above: Soban. Red lacquer on wood inlay with mother-of-pearl. H. 39cm, Diameter: 62,8cm

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Lacquered wood. Joseon dynasty, 19th century.

Collection: Tokyo National Museum.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Items of red and black lacquered furniture, like this tiger-legged dining table, were generally used by the royal family. The top of this dining table is shaped like a dish, which is also a feature of the small dining tables used within the palace. The wood ornament supporting the top is adorned with openwork scroll designs.

This is a red lacquerware table decorated with a dragon motif. The upper surface features a gold depiction of two dragons holding a giant orb, known as the ‘yeouiju’ (여의주). A gold ivy pattern adorns the bottom. The wind holes are engraved with arabesque designs. The characters ‘萬歲’ (meaning ‘ten thousand years’) are engraved on the left and right, while ‘聖壽’ (meaning ‘sacred longevity’) are engraved on the front and back. The legs are shaped like tigers and include a footrest.

H. 91cm, W. 48cm.

Fine linen-covered pine wood and black lacquer was applied to it.

In the lower part of the front, a scene where two dragons fight over a cloudy sky, and grass and insect patterns are decorated in a balanced way between them.

Other parts were decorated with grass and insect patterns on black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay.

Given its elegance, it is presumed that this chest was used by the royal court. Collection of the Gyeonggi Provincial Museum.

Red lacquer on wood.

H. 143cm, W. 116,5cm, D. 56,3cm

Featured in an auction in Seoul Korea and sold for KRW. 37,000,000.- in 2011

H. 114,5cm, W. 64,3cm, D. 37,3cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

Yellow brass fittings. 18th – 19th century

H. 180,5cm, W. 108,3cm, D. 62,3cm. This three level clothing chest with bamboo mat design is a piece of furniture that suits the grace and dignity of the royal court. Collection: National Museum of Korea.

L. 365.5 cm, (Seat) 72.7 cm, W 63.6 cm, H 69.6 cm. Collection: The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon. USA.

Litters for transporting a person are roughly divided into palanquins with roofs and columns to protect the occupant (yuok-gyoja 有屋轎子) and open sedan chairs (pyeong-gyoja 平轎子) with low railings and a backrest. The four-legged base of this chair is decorated with large openwork plant scrolls spandrels beneath its horizontal carrying poles. The backrest is centered by an embossed-carved panel with the sun supported by clouds and twin phoenixes, surrounded by openwork peony scrolls. Panels of the lower tier of the seat railing are each carved with the herb of eternal youth (bullocho 不老草) in an openwork yeoiuidu 如意頭 (Ch. ruyitou) cartouche and lined with another panel. Panels of the second tier around the three sides of the seat show the finest embossed-carving technique through a series of peony motifs in two layers. The third tier forming the backrest is openwork carved with dragon scrolls in four panels, and the fourth tier is openwork carved with repetitive coin patterns without dividing panels. Large iron fittings are attached where the bulky wooden frames join and are decorated with various silver-inlay patterns such as the Chinese character “su 壽” (longevity), peony scrolls, various lines, and curves. Large tin strip fittings with inverse-chased plant scrolls adjoin the seat railing parts at the edges, and chrysanthemum-headed T-fittings fasten the inner latticed structures. This sedan chair is thickly lacquered in black with major decorative patterns highlighted in vermillion for brilliance. It was presumably used at the royal court or in an elite household.