Lacquer, known as “ottchil” (옻칠) in Korean, is a natural paint that has been utilized in Asia since ancient times. Its properties, such as water and insect repellency, enhance the durability of objects while imbuing them with a beautiful luster.

The application of lacquer is a time and labor-intensive process. Initially, it takes several months to extract lacquer from the tree, purify it, and transform it into paint. Subsequently, the production demands even more patience, involving repeated painting and drying processes.

The technique of using lacquer originated in China over 3000 years ago and later spread eastward to Korea and Japan. Lacquer is a significant art form in Korea.

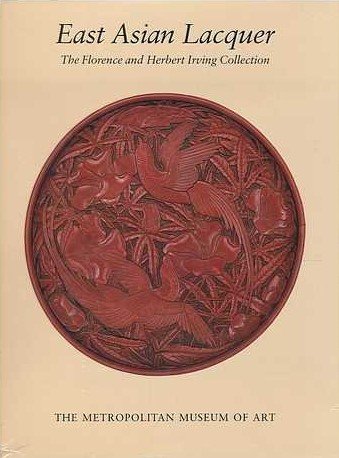

“The history of lacquerware in Korea goes back at least two thousand years. However, as with China, all the lacquer objects dating from prehistoric times to the eleventh century have been obtained from archaeological excavations and are not in a good state of preservation. Moreover, of the few reasonably well-preserved lacquer pieces from the Goryeo and early Joseon periods (about the 10th to the 16th century), the great majority are no longer in the country. At present fewer than fifteen pieces of Goryeo lacquer are known to have survived above ground; most are in Japanese collections, and those in Western museums all came from Japan. These works have been the object of intermittent attention from Japanese and Western scholars over the past forty years. As to the early Joseon group, the material is so widely scattered and the criteria for dating, in spite of preliminary efforts by a number of scholars, are so vague that it has not yet been possible to define the group, let alone make a count of it. This paucity of material is largely attributable to the fragility of lacquer objects and, to a certain extent, to wars and raids by foreign powers, notably the one launched from Japan by Hideyoshi in the late sixteenth century. It is not the case, however, that all the early Korean lacquers in Japan arrived in the form of loot or war booty. The Japanese preserved not only Korean works but also nearly all the extant Chinese lacquer dating from the 14th century and earlier. Most of these pieces arrived as gifts or as items of trade, and others were brought back to Japan by Buddhist monks and lay visitors. Lacquers of the middle to late Joseon period are plentiful and there is little difficulty attached to their identification and dating.” EAST ASIAN LACQUER: the Florence and Herbert Irving collection / by James C.Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford.

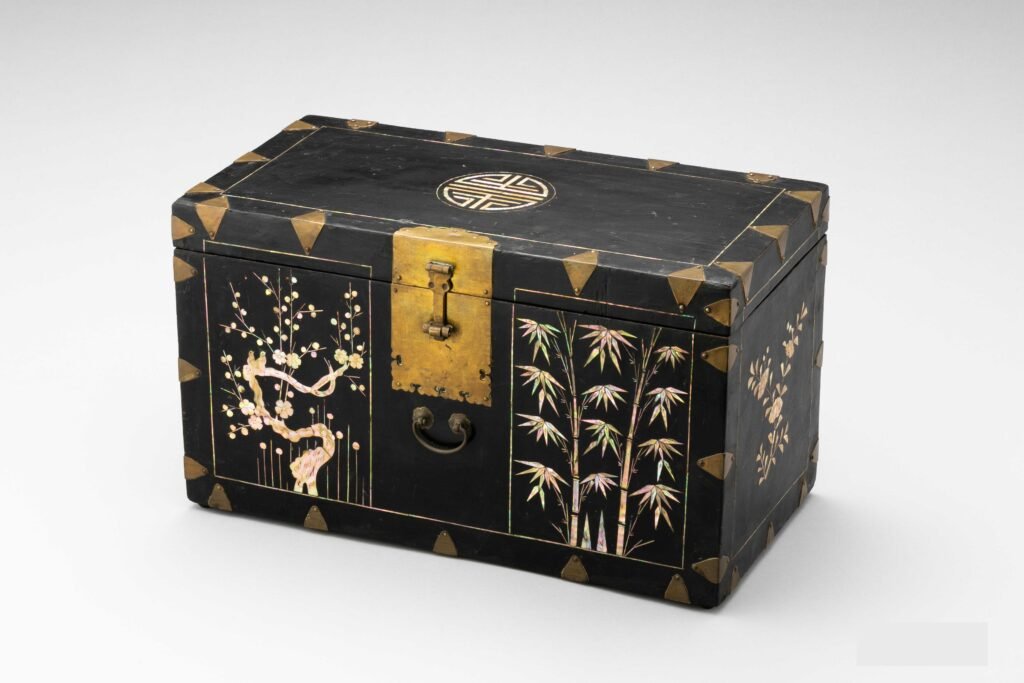

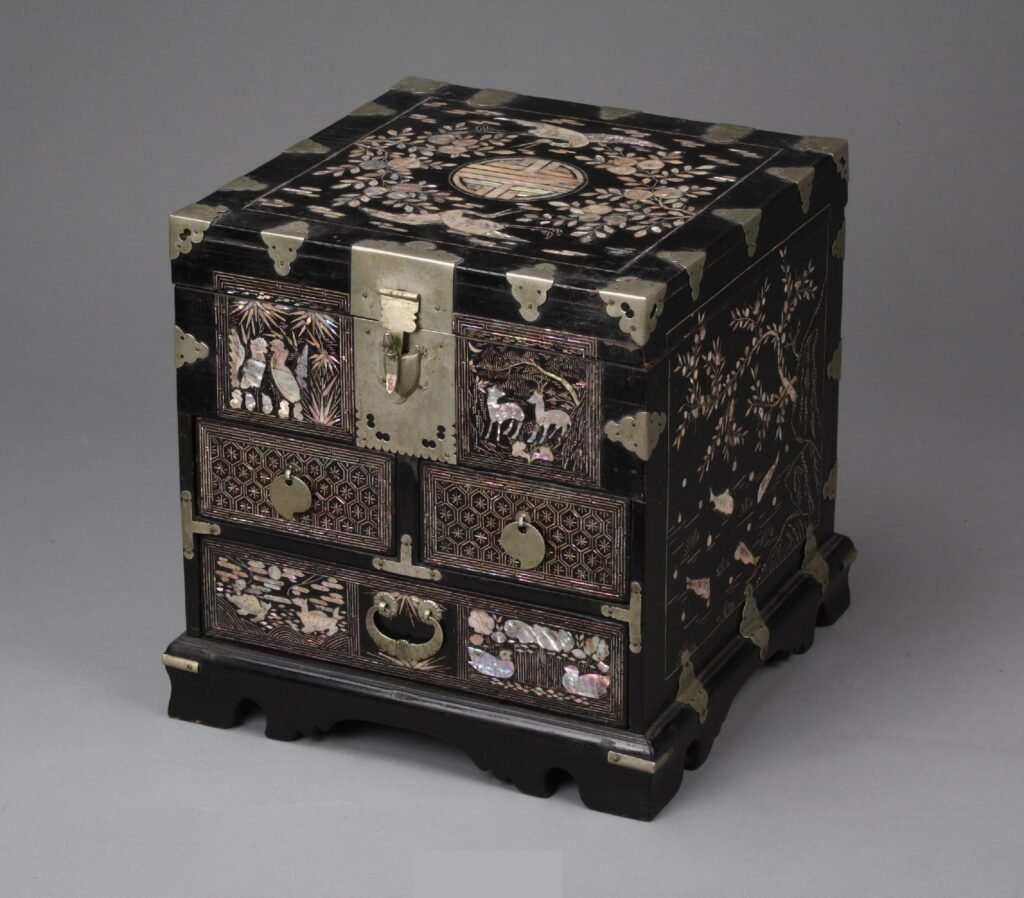

Lacquer inlaid with mother-of-pearl and tortoise shell over pigment and brass wire

Dimensions: H. 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm); L. 4 in. (10.2 cm); D. 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm). Collection of the MET. Metropolitan Museum. USA.

LACQUER IN KOREA.

While drawing inspiration from Chinese techniques, Korean artists also developed their own innovative methods.

Lacquerware is crafted by layering processed sap from the lacquer tree onto a core made of wood, bamboo, or other materials. Each thin layer must fully dry before applying the next, resulting in a product that is resistant to heat and moisture. Pigments can be mixed into the lacquer to create various colors on the finished piece. Due to the numerous layers involved and extended drying times, a single piece can take several months or even up to a year to complete.

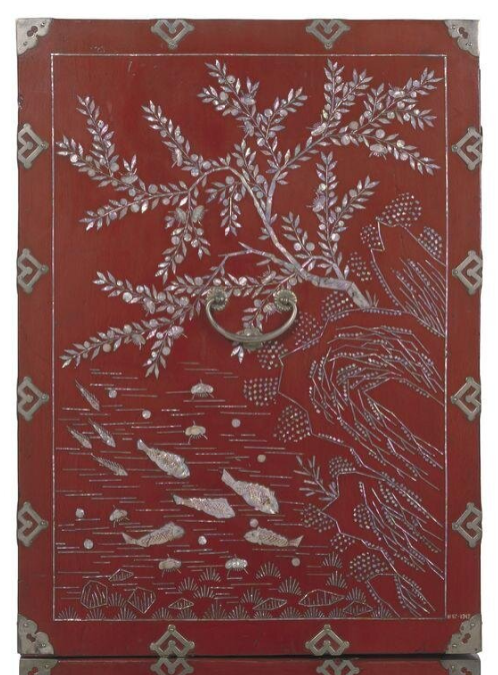

This technique provided a glossy, decorative surface for furniture. However, because red lacquer was a costly pigment, it was primarily used for ceremonial items in the royal palace.

Red lacquer, also known as “juchil“, is prevalent in lacquerware due to the historical association of the color red with good fortune. In the Joseon Dynasty, both royal family members would typically carry at least one red item, either in their clothing or accessories, when attending important events. According to Edward Reynolds Wright and Man Sill Pai in their excellent publication “Korean Furniture, Elegance and Tradition,” red lacquer (Chu-Ch’il) is a refined lacquer mixed with either iron oxide or cinnabar pigments or a combination of both. Colored lacquer was applied over an undercoating, often using persimmon tannin.

However, red lacquer, being an expensive pigment, was primarily reserved for ceremonial items in the royal palace.

H. 27cm, W. 36cm, D. 23cm. Collection of the National Museum of Korea.

Collection of the National Museum of Korea.

Collection: Hwaseong City History Museum, Gyeonggi Do.

Lacquer on wood with inlaid mother-of-pearl and metal fittings. H. 137,5cm, W. 73,8cm, D. 36,8cm. During the Joseon dynasty, a red-lacquer chest such as this was for upper-class women. Collection of the San Francisco Asian Art Museum, USA.

Height: 136,3cm, Width: 84cm, Depth: 48,5cm. East Asia Collection Victoria and

Albert Museum. Great Britain.

During most of the Choson dynasty (1392-1910) strict sumptuary laws limited the use of red lacquer by the royal household. By the 1890s, however, these rules lapsed and customers of non-royal descent were able to order lavishly decorated red lacquerwares. This chest, used for storing clothes, is inlaid with auspicious motifs in mother-of-pearl, featuring on the front phoenixes, cranes and pheasants among foliage. The metal fittings are in the form of butterflies, stylised flowers and lucky emblems, made of an alloy of nickel, copper and zinc known as paktong. The two sections are not joined but simply rest on each other. Underfloor heating was popular in Korea, then as well as now, and the stand protected the chests from the heat.

A storage chest for clothing formed of two chests of similar design supported on a base. The base protects the lower chest from the under-floor ondol heating which is a feature of traditional Korean homes. The mother-of-pearl designs depict cranes, phoenixes, and pheasants amongst foliage, in a border of lucky emblems. The metal fittings are in the form of butterflies and stylised flowerheads. Chests covered in red lacquer were usually owned by members of the royal family or high-ranking aristocrats.

The Nong (stacking chest) is one of the most representative interior furniture along with the Jang (cabinet). The Nong is different from the Jang in that it consists of separable chests stacked together. The legs are decorated with scroll patterns. The top panels of the two chests are inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and it seems that there was a ring between the two chests. The front is adorned with designs symbolizing longevity and wealth such as plums, birds, heavenly peaches, mandarin ducks, phoenixes, and Seven Treasures, while the sides are embellished with rocks, fish, and willows. The back is decorated with broken pieces of mother-of-pearl and lacquered in red. Handles are attached to the front and sides. The lock with the inscription of the character “囍”(hui), meaning double happiness, is attached to the front on the metal plate in the shape of a butterfly; the key does not match the lock. There are inner sliding doors. The inside of the chest is lined with white paper, and the inner side of the doors is lined with red paper. This type of stacking chest is similar to those produced for the usage of the royal family during the Korean Empire.

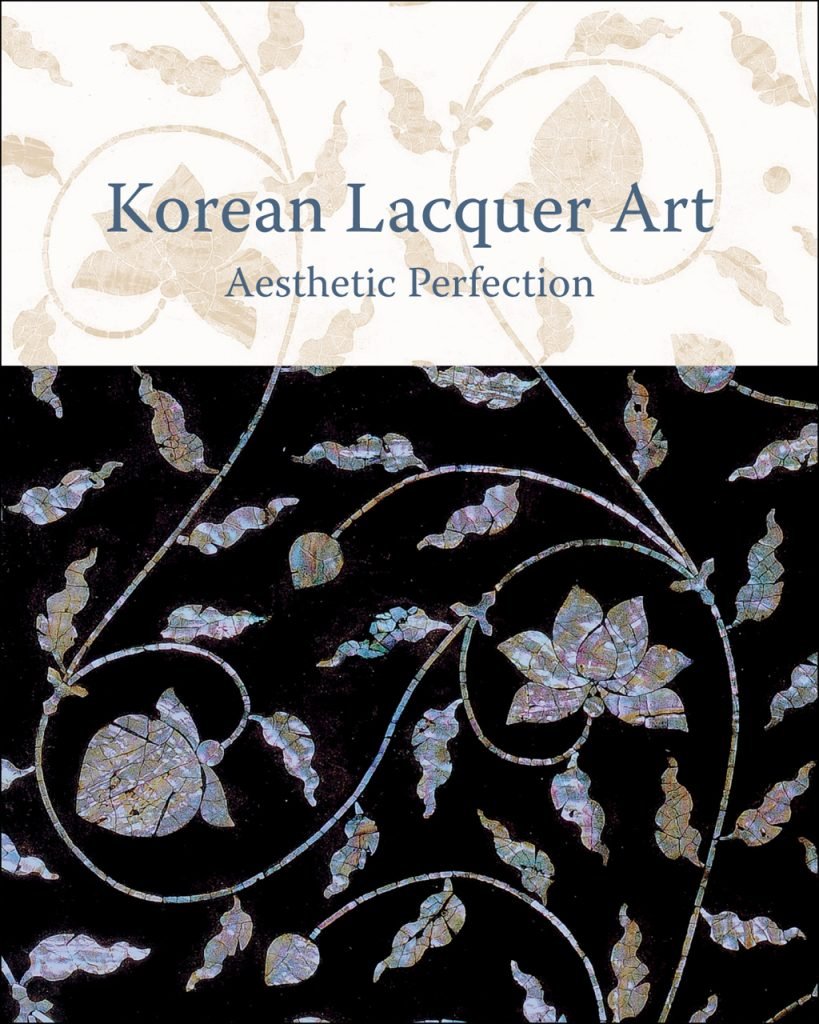

MOTHER-OF-PEARL INLAY.

The technique of mother-of-pearl inlay, known as “najeon,” also originated in China, and historical evidence suggests that this technique had reached the Korean peninsula by the eighth century.

This traditional art of mother-of-pearl inlay on lacquerware requires a high level of skill. Creating a single piece involves woodwork, metalwork, lacquer techniques, as well as mother-of-pearl carving and inlay.

Today, mother-of-pearl inlay is a prominent feature of Korean lacquerware. In this technique, the thin inner layer of shells, such as abalone, is meticulously cut and inlaid onto the lacquerware. Sometimes, the design is layered on top of the numerous base coats of lacquer and coated until it’s submerged. Then, the top layer of lacquer is carefully sanded down to reveal the mother-of-pearl. Alternatively, the design is carved into the surface, and the material is inset, followed by the application of more lacquer and further sanding. Occasionally, other materials like metal, tortoiseshell, or sharkskin are used alongside the mother-of-pearl. Artisans during the “Goryeo” period (918–1392) introduced copper-alloy wires in their inlay designs, a unique feature of Korean lacquerware. Typically, only the visible surfaces of an object are decorated, while the inside of a box, for instance, is usually left unadorned.

During the “Goryeo” period (918–1392), lacquerware was highly esteemed among the elites and was primarily produced in connection with Buddhist practices. Production was monopolized by the imperial workshop. However, during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), lacquer became more widely accessible and began to be applied to secular objects as the influence of Buddhism waned. The expansion of “najeon” use also led to the incorporation of new design motifs, including auspicious plants, animals, and mythological figures.

Late 19th century. L. 17cm, W. 7 cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

19th century. H. 4,9cm, W. 9,5cm, D. 4,6cm.

Collection National Museum of Korea.

H. 28cm, W. 47cm, D. 27cm.

Collection: Eunpyeong History Hanok Museum, Gyeonggi Do.

Collection: National Folk Museum. Seoul.

H. 102,8cm, W. 73cm, D. 34,7cm.

The cabinet is a red-painted structure with three levels, decorated with mother-of-pearl patterns. The first and second levels have doors that swing open. The third level is open, supported by four pillars and a roof. The roof has curled edges and shows a large rock with trees. The third level’s shelf depicts a river scene with a boat. The doors on the first two levels have frames to keep them straight. They have metal handles and side panels, with a ring on the right side for locking. The doors are decorated with metal wire and show similar scenes: a man meeting a wise person on a boat. The second level shows people sitting under a pine tree, while the first level shows someone standing under a willow tree, with a house and clouds across the river. Collection: Busan Metropolitan City Museum.

Gyeongsang Do province.

Collection: Busan Metropolitan City Museum.

SHAGREEN – RAY SKIN INLAY

The top surface of each piece of ray skin inlay on all the objects was sanded before being used to create a smooth surface.

Each piece of ray skin inlay is backed with a finely woven plain weave textile attached with a clear adhesive. The purpose of this backing textile remains uncertain. It may serve to provide a consistent surface for adherence to the substrate. The ray skin inlay was most likely processed by dyeing the skin and textile separately, bonding them together, and subsequently cutting out individual inlay pieces.

19th century.

Lacquer inlaid with mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, ray skin, and brass wire

Dimensions: H. 10 1/8 in. (25.7 cm); W. 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm); L. 24 3/8 in. (61.9 cm).

Collection of the MET. Metropolitan Museum of Art. USA.

TORTOISESHELL INLAY

The procedure for plating tortoiseshell was similar to that of shagreen. It was also backed with a textile.

WIRE INLAY

Single and twisted wire inlays are employed to embellish the surface of the item. They function as borders for other design elements, and at times, they are used to craft standalone organic curving shapes as design elements. In both cases, it is evident that both types of wires have been abraded after application, resulting in a flat upper surface.

ASSEMBLY.

While practices may vary, the general process typically involved several steps. First, the wooden structure was prepared, followed by the attachment of a textile base layer, usually made of hemp. Subsequently, the inlay elements were affixed to this textile base layer. Examination of cross-sections from the objects indicates that a bulked lacquer ground layer was then applied, followed by one or two thin lacquer layers. The final step involved meticulous polishing to reveal the design.

INTERESTING LINKS:

Shell and Resin: Korean Mother-of-Pearl and Lacquer

Korean Mother-of-pearl inlaid lacquerware.

Korean lacquer box

How was it made? A Korean lacquer vessel

Korean Lacquerware from the Late Joseon Dynasty: Conservation and Analysis of Four Objects at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco