LE MUSEE GUIMET

The largest collection of traditional Korean art is housed in the Guimet Museum, located at 6 Place d’Iéna in Paris. This museum was founded by Émile Guimet (1836-1918), an art collector with a deep passion for Asian cultures.

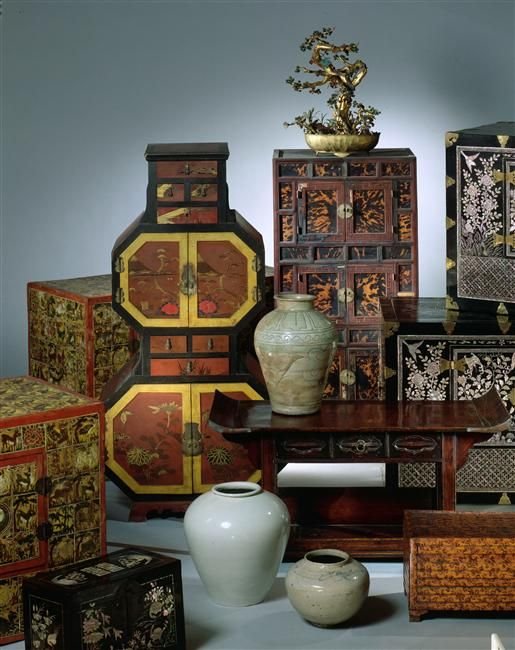

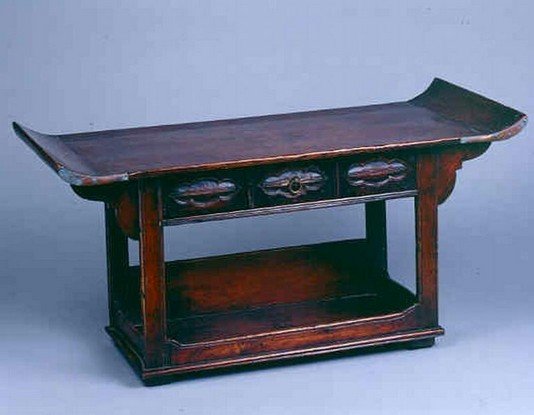

The history of the collection dates back to 1888 when Charles Varat (1842-1893), a French explorer dispatched by the Ministry of Public Education and Fine Arts to Korea for ethnographic and anthropological research. In collaboration with Victor Collin de Plancy (1853-1922), a French diplomat in Seoul, they collected Buddhist and shamanic paintings, sculptures of Buddha or Bodhisattva made from wood, bronze, or cast iron, as well as costumes, masks, and furniture.

Charles Varat and the Korean collection at the Musée National des Arts asiatiques – Guimet.

In 1888, Charles Varat (1842/43-1893) traveled to Korea on a mission for the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts. A wealthy Parisian, he was keen on exploration and anthropology. After several trips to Russia and Scandinavia, his goal was to discover Korean culture. At the time, China and Japan were well known in France. Nothing was known of Korea, however. Two years after the treaty of friendship between France and Korea, Charles Varat felt that the time had come to go there, especially as the first contacts between the two countries twenty years earlier had been violent, when Admiral Roze’s expedition to the island of Kanghwa-do had tried to put pressure on the regent Taewon’gun to put an end to the bloody repression carried out against Catholics, and in particular the missionaries of the Société des Missions étrangères de Paris.

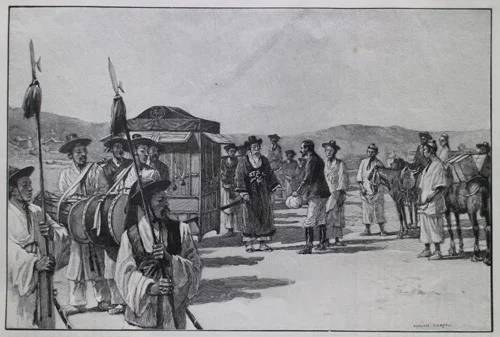

With the help of Victor Collin de Plancy, the first French diplomat at the Seoul court, who had just arrived, and the support of the Korean government, Varat embarked on a policy of buying everything he could think of that was Korean, in order to raise awareness in Paris of Korea’s identity. The collection he built up during his trip was fairly eclectic, including Buddhist and shamanic paintings, Buddha and Bodhisattva sculptures in wood, bronze and cast iron, as well as costumes, masks and furniture. In 1889, it was exhibited at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, but Varat insisted that it should remain accessible to the public, and in 1891 it was assigned by the Ministry to the brand-new Musée Guimet, created three years earlier as the Musée National dedicated to Asia, the same year that the Eiffel Tower rose into the Paris sky.

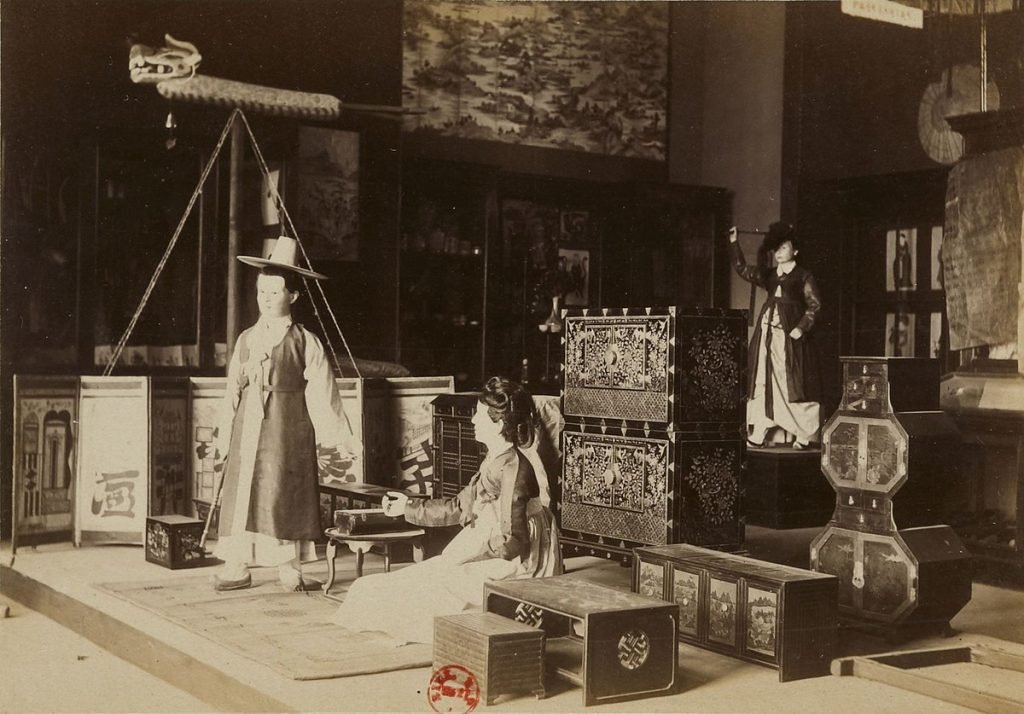

In 1893, a Korean gallery was opened on the second floor of the Museum, organized, classified and set up by Charles Varat, assisted by Hong Jeong-Ou, one of the very first Koreans to come to Paris, whom Félix Régamey put in contact with Emile Guimet. From Seoul, Victor Collin de Plancy sent furniture and ceramics to complete Varat’s acquisitions, but Varat died suddenly the same year, while preparing a book on Korea, when Hong Jeong-Ou, back in the East, assassinated Kim Ok-kyun in Shanghai in 1894, the author of the failed coup d’état of 1884, precipitating the crisis that would lead to war between China and Japan.

Later, Collin de Plancy, again appointed to Korea (1896-1906), would send some Buddhist paintings in response to Guimet’s wishes. Perhaps among them was the beautiful banner from Konbongsa, dated 1755, which evokes the “Ambrosia of the Law” (Amrita raja), the “festival of souls”, evoking Korean society at the feet of the seven Buddhas, symbols of the Big Dipper and impermanence. This painting was exhibited in the pavilion of the Korean Empire (1897-1910) at the 1900 International Exhibition in Paris, alongside objects sent from Korea and from French collections, starting with that of Collin de Plancy. Korea aroused sympathy and curiosity in France, and Edouard Chavannes himself travelled from Peking to the Korean border, to reconnoitre the remains of the Koguryo kingdom. However, after 1918, the death of Emile Guimet, the Japanese annexation and the first general renovation of the museum, Korea all but disappeared from the galleries. It only timidly reappeared after 1945, with the transfer to the museum of the Louvre’s Asian collections (Bodhisattva méditant, gilded bronze, perhaps from the Paekche, Hayashi sale; Avalokitesvara à la lune, Koryo painting, former Takahashi collection or Punch’ong ceramics from the Raymond Koechlin bequest). It was also at these dates that the Silla crown was acquired in Tokyo, and that Mme Louis Marin donated a superb screen on the theme of genre scenes, signed by Kim Hong-do, as a souvenir of her husband’s trip to Seoul in 1901, not forgetting the very fine Koryo celadons from the Michel Callman bequest. The Korean collections, in fact, were redeployed in 2001, when the museum underwent its second general renovation. However, these collections were duly supplemented by new acquisitions (painting by Yi Chong, portrait by Yi Han-ch’ol, Koryo bronzes, etc.) or donations (Lee Ufan collection, Itami Jun donations, Joseph and Roberta Carroll collections).

Pierre Cambon. Chief Curator, Guimet Museum, Paris France. http://www.guimet.fr/fr

H. 13.cm, W. 53cm

H. 31cm ; W. 77cm, D. 24cm.

H. 45cm, W. 90cm, D. 45cm.

H. 28cm, W. 22cm, D. 22cm.

H. 49cm, W. 81.2cm, D. 38,5cm.

H. 102cm, W. 40cm, D. 30cm.

H. 145cm, W. 70cm, D. 45cm.

H. 102cm, W. 81cm, D. 41cm.

H. 50cm, W. 78cm, D. 40cm.

Excerpt from an article published by the Guimet Museum.

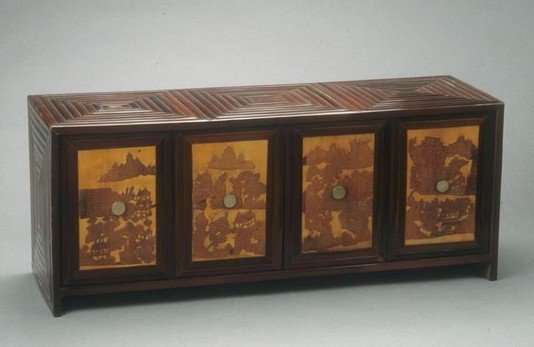

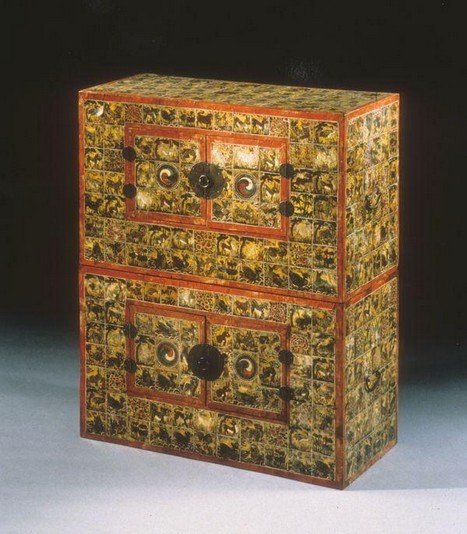

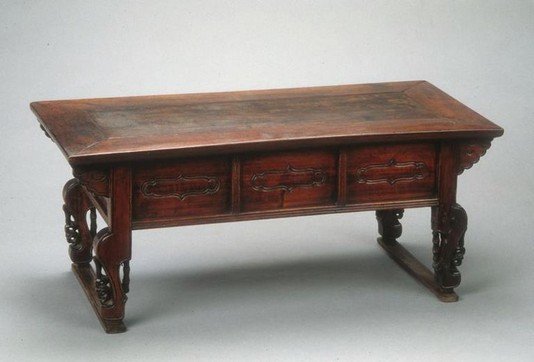

As direct contact with Europeans increased at the end of the 19th century, Korea was treated more as an ethnological subject through research on the Far East regions dedicated to China, Japan, Vietnam, and Korea. Objects from these regions were initially collected based on this interest. The French ethnologist Charles Varat (1843-1893) was the first to display a collection of Korean objects in Europe during the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle. These objects were gathered during his mission to the Korean peninsula the previous year. He selected unique or appropriate items to showcase the traditional lifestyle of Koreans (Cambon and Musée Guimet, 2001). Therefore, he showed little interest in artistic objects such as paintings, sculptures, or ceramics, and focused more on costumes, religious ritual objects, and furniture. The Varat collection first entered the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro and later joined the Guimet Museum along with other objects from the Far East. In 1893, Charles Varat and Hong Jeong Ou (1850-1913), his Korean assistant, identified, classified, and installed them in an exhibition room at the Guimet Museum dedicated to Korea. This was the first exhibition devoted exclusively to Korean objects by a European museum. Costumes and furniture of the time, genre prints and paintings, Buddhist sculptures, and shamanic paintings were thus displayed.

The exhibition was presented within an ethnographic context, for example, with the staging of a gentleman’s study, a wedding, and a mannequin wearing a bureaucrat’s costume. Although this was the only way for French society, and even European society, to approach the world of Korea, this collection was not exhibited for long. Additionally, there were no permanent Korean specialists operating at the museum. When the Guimet Museum was transformed into the National Museum of Asian Arts in the 1920s, only art objects with aesthetic qualities were exhibited. The majority of the Varat collection, having ethnological qualities as it consisted of religious objects and non-unique pieces, was placed in storage.

Today, most of the remaining relics from Joseon-era houses in the Republic of Korea date from the second half of this period, mainly the 19th century. From the earlier period, very few elements have been preserved; studies must rely on ruins, written documents, and sketches from the time. Consequently, research on this residential space has focused more on houses from the second half of the Joseon period and the stereotypical image of traditional Korean houses associated with them. The Joseon Kingdom opened its doors to foreigners in 1876, thus ending its isolationism.

PUBLICATIONS

LINK: Varat – Voyage en Coree

UPDATE DECEMBER 2023.

After several months of refurbishment, the Korea and Japan rooms are once again open to the public, offering a whole new array of prints, fans, screens, and sculptures.

While a bronze and lacquered wood Buddha mosaic decorates the Japan room, the Korea room features a new showcase, combining Kisan paintings (early 19th-century depictions of everyday Korean life) with scholar’s stones, donated by Min Moung-Chul in 2019.

Starting today at the museum, also discover:

- A selection of sumptuous fans from the Edo period (1603-1868) in the Japan room.

- A magnificent twelve-panel screen from the Choson dynasty (1392-1910), on display for the first time at the museum, in the Korea room.

And many other splendors await!