This brief history of traditional Korean furniture aims to address common questions about its origins and the limited availability of antique pieces in the market.

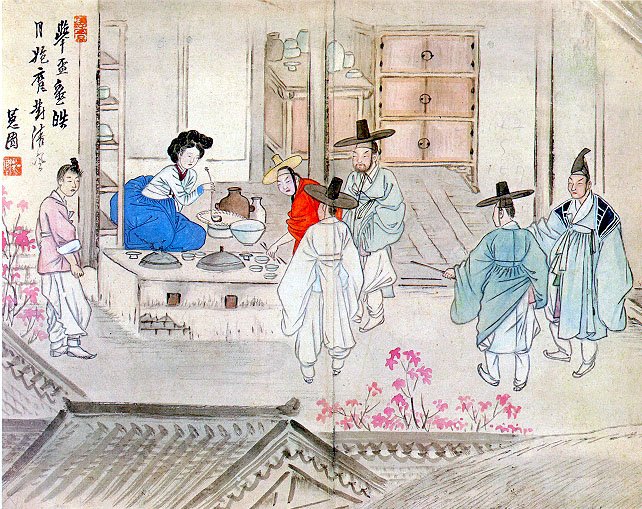

Feature photo at the top of this post: A painting by Shin Yun-bok, who was born around 1758 and passed away after 1813. He was a Korean painter known by the pseudonym Hyewon, with the courtesy first name Ipbu. Like his colleagues Danwon and Geungjae, he is renowned for his depictions of everyday life.

The history of Korea is relatively unknown in the Western world, primarily because Korea remained isolated from the outside world for an extended period of time. Korea was known as the “Hermit Kingdom”.

THE JOSEON DYNASTY 1392 – 1897

Joseon was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom was founded following the aftermath of the overthrow of Goryeo in what is today the city of Kaesong. Early on, Korea was retitled and the capital was relocated to modern-day Seoul. The kingdom’s northernmost borders were expanded to the natural boundaries at the rivers of Amrok and Tuman through the subjugation of the Jurchens.

During its 500 year duration, Joseon encouraged the entrenchment of Confucian ideals and doctrines in Korean society. Neo-Confucianism was installed as the new state’s ideology. Buddhism was accordingly discouraged, and occasionally the practitioners faced persecutions. Joseon consolidated its effective rule over the territory of current Korea and saw the height of classical Korean culture, trade, literature, and science and technology. In the 1590s, the kingdom was severely weakened due to Japanese invasions. Several decades later, Joseon was invaded by the Later Jin dynasty and the Qing dynasty in 1627 and 1636–1637 respectively, leading to an increasingly harsh isolationist policy, for which the country became known as the “hermit kingdom” in Western literature. After the end of these invasions from Manchuria, Joseon experienced a nearly 200-year period of peace and prosperity, along with cultural and technological development. What power the kingdom recovered during its isolation waned as the 18th century came to a close. Faced with internal strife, power struggles, international pressure, and rebellions at home, the kingdom declined rapidly in the late 19th century.

During the 500 years Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), there was little exchange with the outside world. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the first missions reached its shores.

It is, therefore, easy to understand why traditional Korean furniture, in particular, became “popular” only much later, certainly long after Chinese or Japanese furniture.

The current examination of traditional Korean furniture does not solely focus on the final years of the Joseon dynasty. However, it is indeed challenging to find information and furniture from before the 19th century.

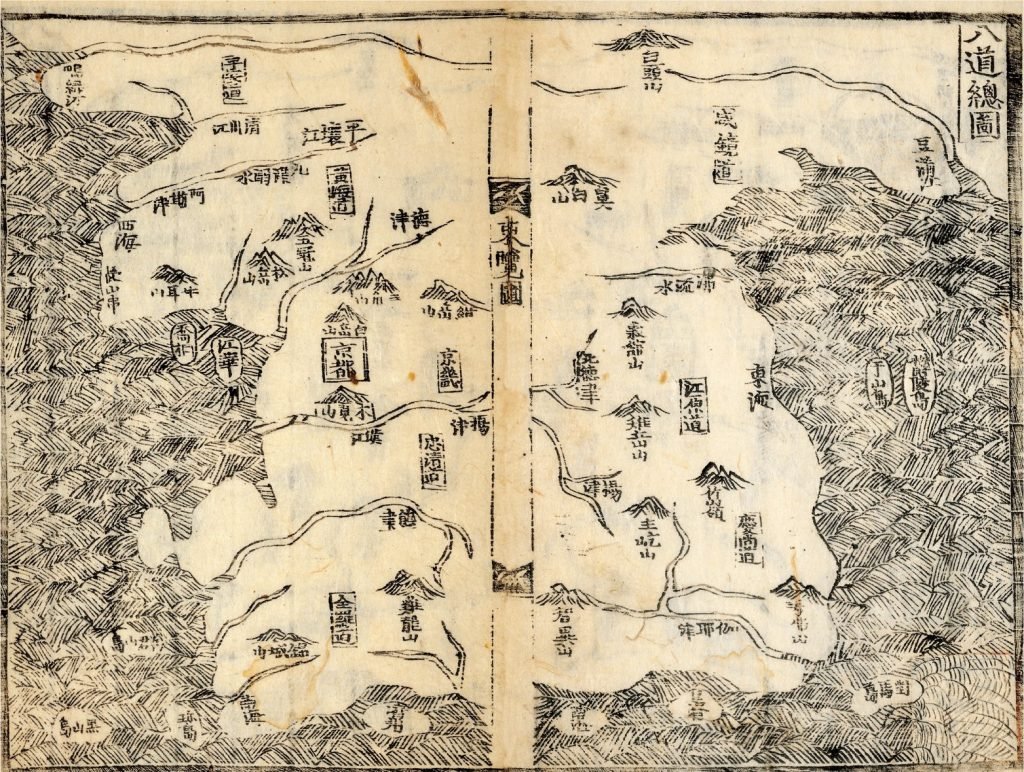

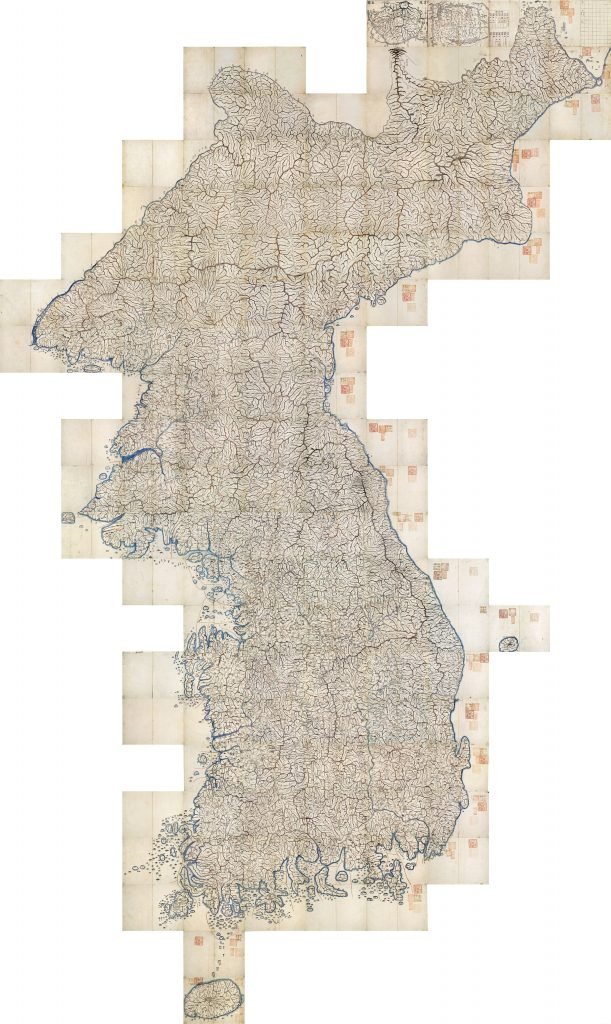

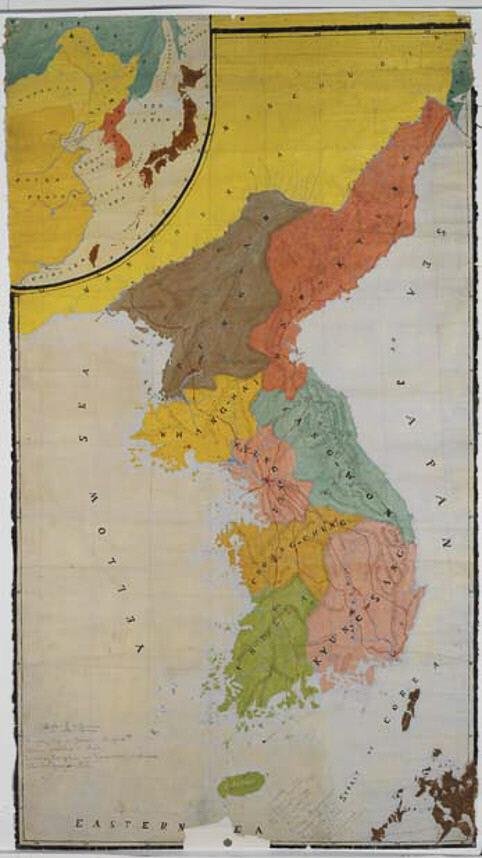

Korea, as we recognize it today, is divided into two at the 38th parallel. Nevertheless, in this study, we portray it as a unified entity, as it was during the Joseon dynasty with its eight provinces.

KOREAN DURING THE JOSEON DYNASTY.

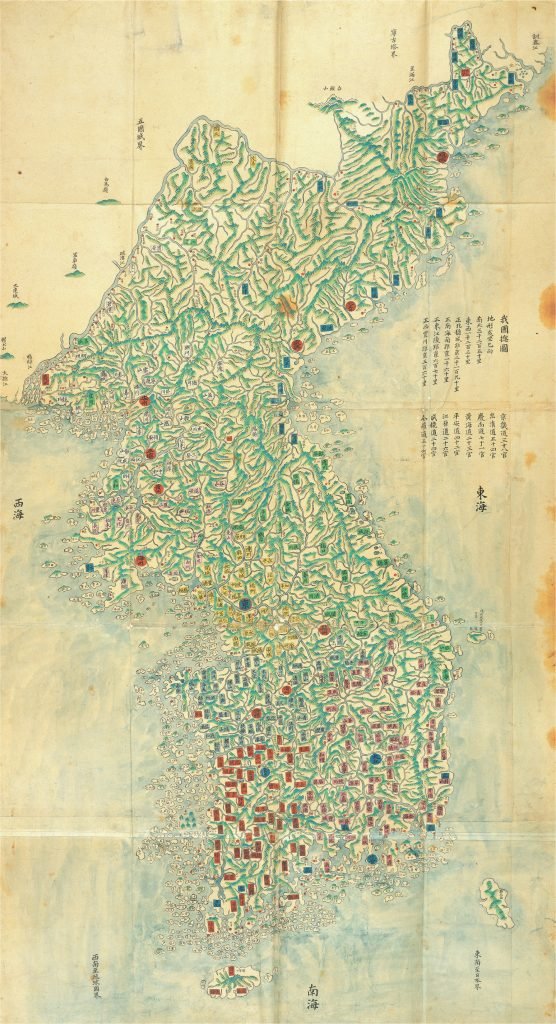

Ink and color on paper. Date:1885 – 1910 AD

Period: Joseon Dynasty. Dimension:126 × 70.3 cm.

Collection Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

THE EARLY YEARS.

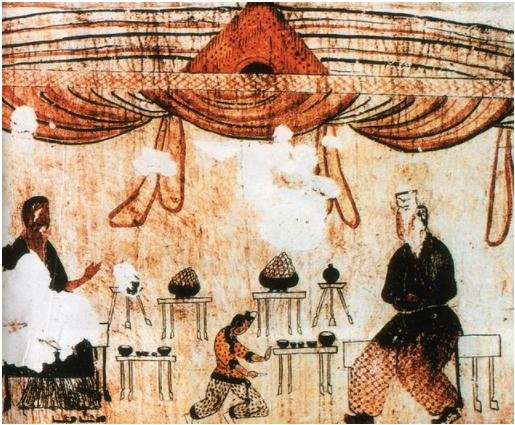

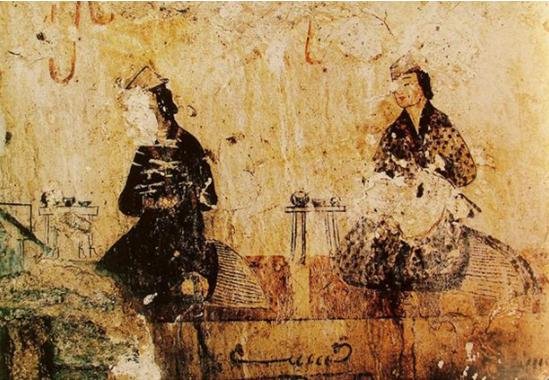

The mural paintings on the tombs walls of the Goguryeo Kingdom (37 BC – 668 AD) such as Ssangyeongchong, Muyongchong, Sashinchong, and Gakjeochong aid us in deducing the living conditions of those times, as they depict wooden benches, chairs, and tables.

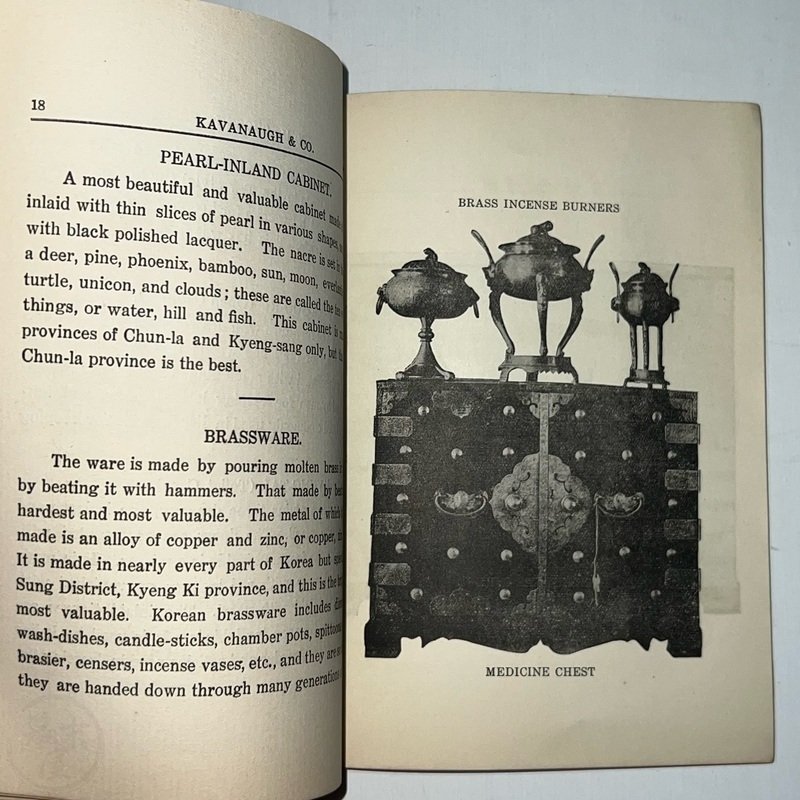

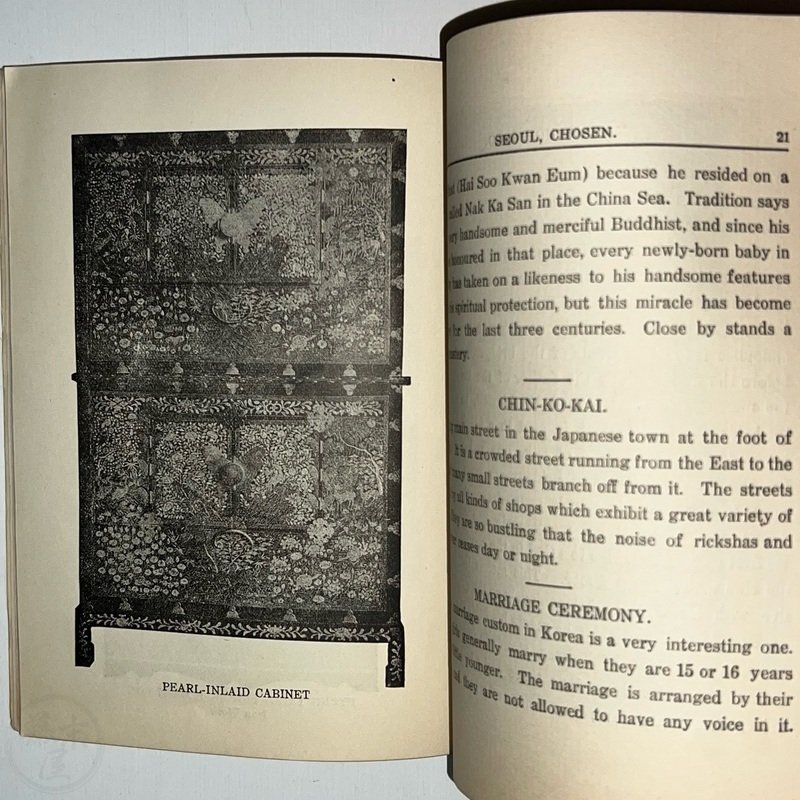

Most relics found in tombs of the ancient Three Kingdoms are Najeonchilgi (lacquerware) and were used by upper-class families.

Goryeo dynasty – 12th century

Lacquered wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl

H: 4,5cm, Diam.: 12,4cm.

Taima-dera Temple

In Korea, abundant wood resources have been available for a long time, as large parts of its territory are covered by wooded mountain areas. People have traditionally built wooden houses to live in and used wood to make their utensils and work tools.

According to “Sinjeung-Dongguk-Yeojiseungram,” a geography book compiled in 1530, there were stores that sold a variety of wooden products, including boxes, windows, chests, wardrobes, and paper cabinets.

HANOK – INSIDE THE KOREAN HOUSE.

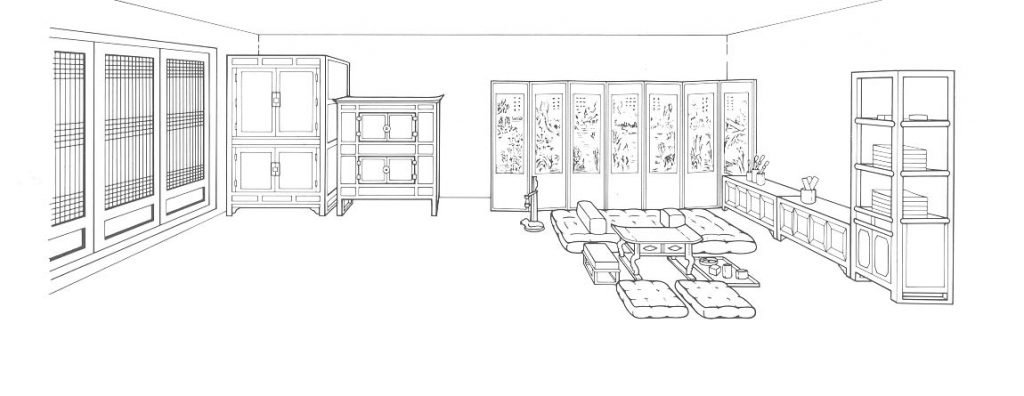

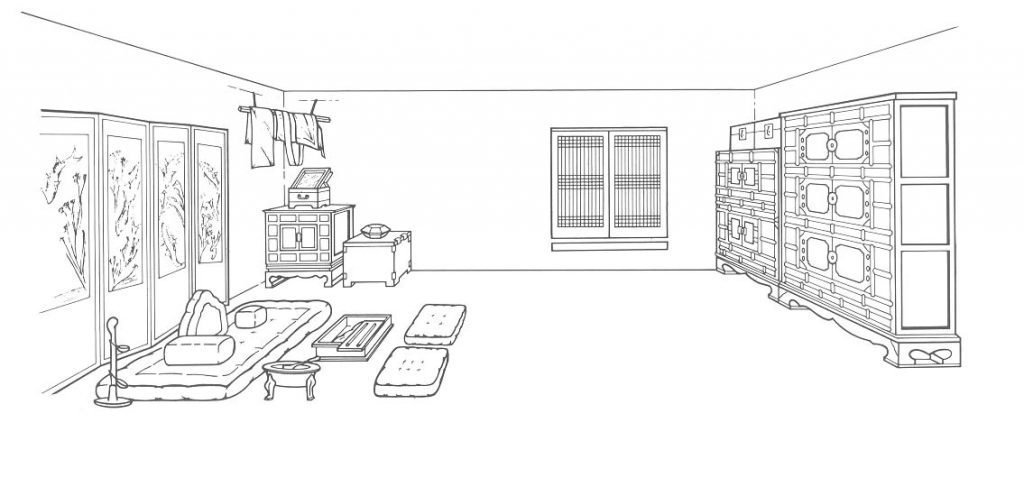

During the Joseon dynasty, the residential space in the Hanok (Traditional House) was divided in accordance with Neo-Confucian ideas. According to its principles, the genders (male and female) lived separately within the domestic space.

The women’s quarters were called “anch’ae“, and the inner room (bedroom) was called an “anbang“. Men’s quarters were referred to as “sarangch’ae“, and the main room as the “sarangbang“, which was mainly used for studying and receiving guests.

Traditional furniture was categorized based on the space in which it would be used: “anbang” furniture for the women’s quarters and “sarangbang” furniture for the men’s quarters.

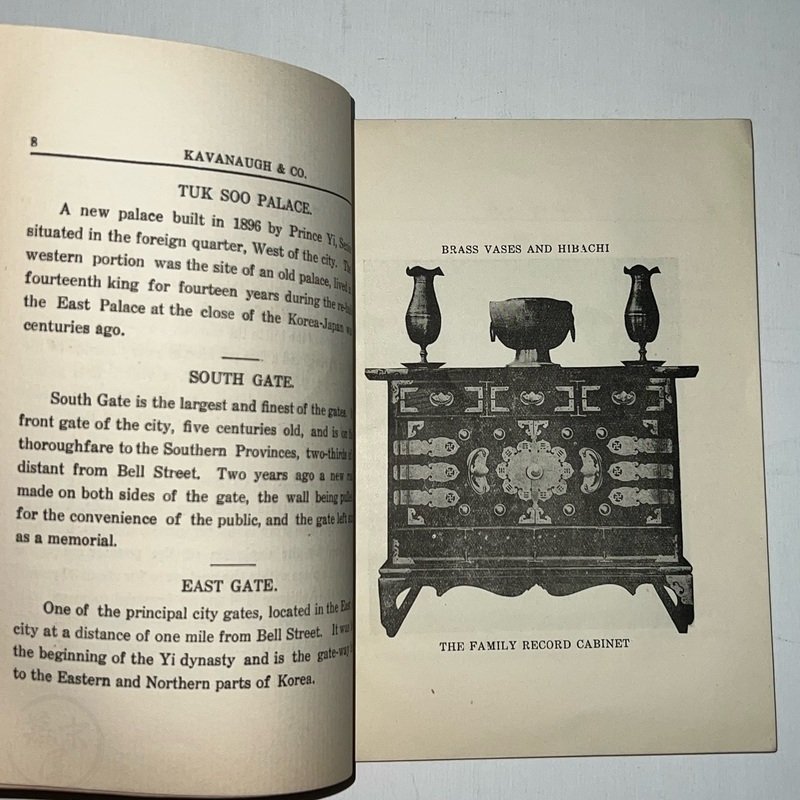

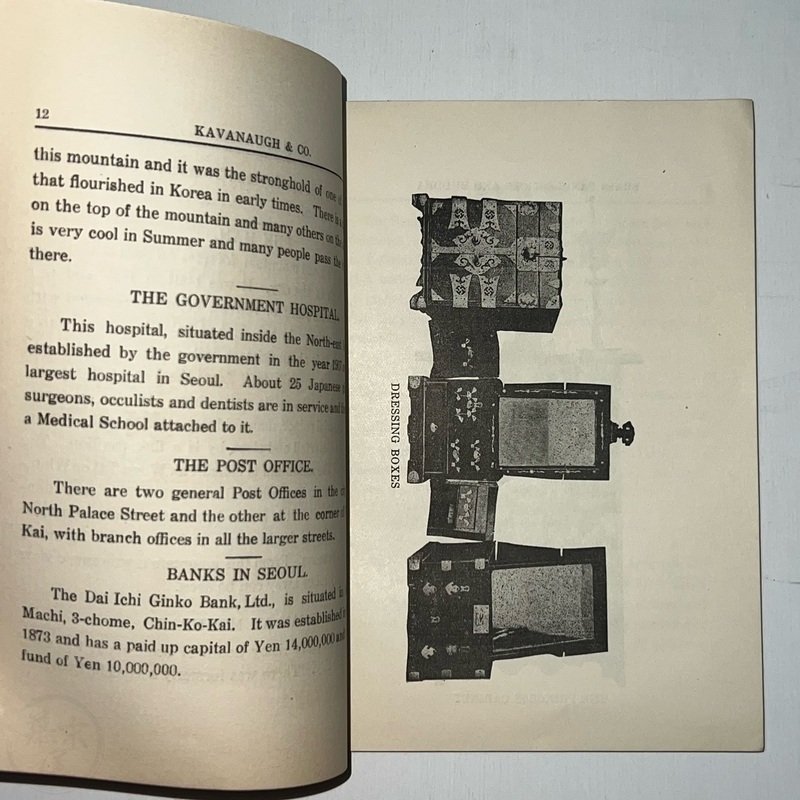

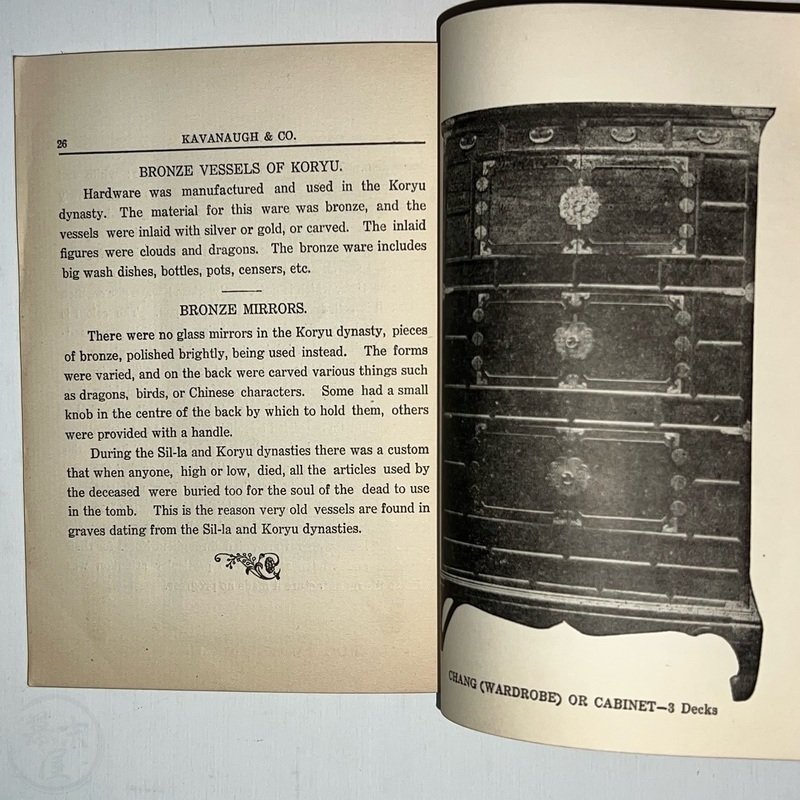

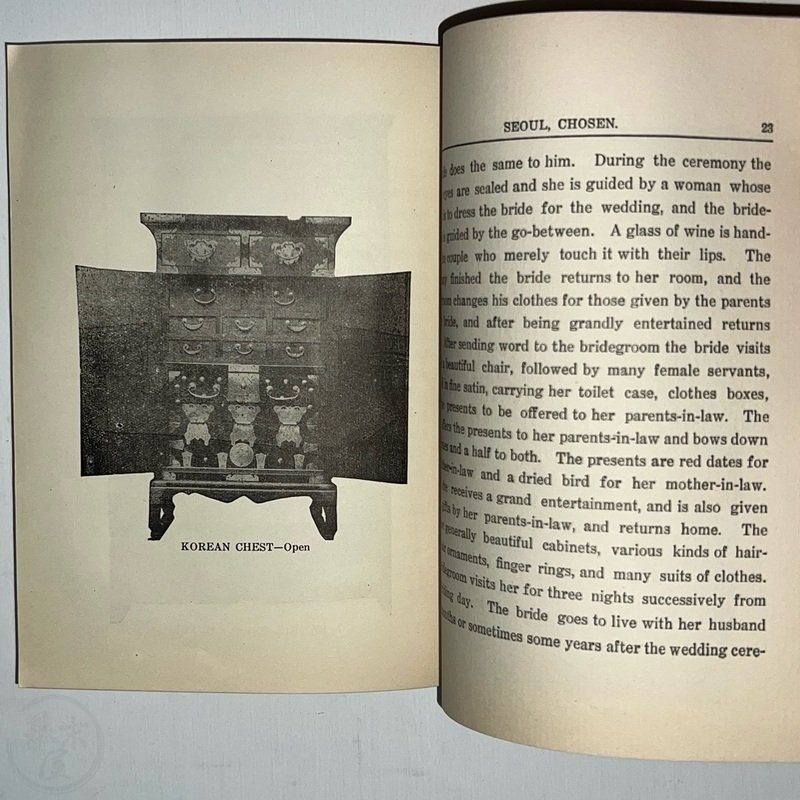

The “anbang” typically housed storage furniture, such as clothing chests (Jang with different levels). These chests were often elaborately decorated with favored colors and attractive metalwork plates. In contrast, furniture from the “sarangbang” was more restrained, with less decoration to showcase the wood’s natural grain. The colors were darker.

TESTIMONIALS

The study of the origins of traditional Korean furniture is challenging due to the lack of adequate documentation.

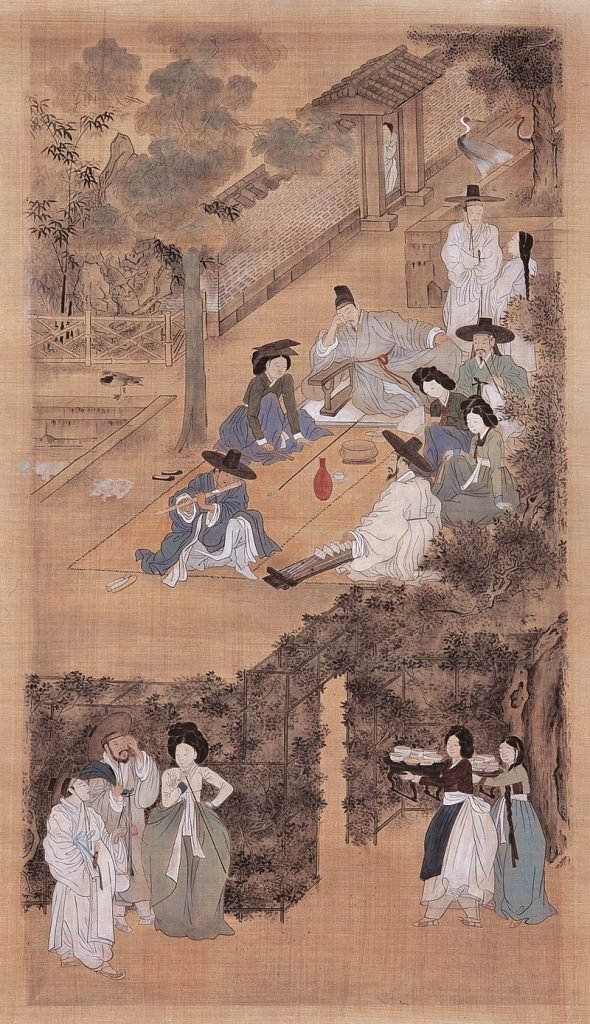

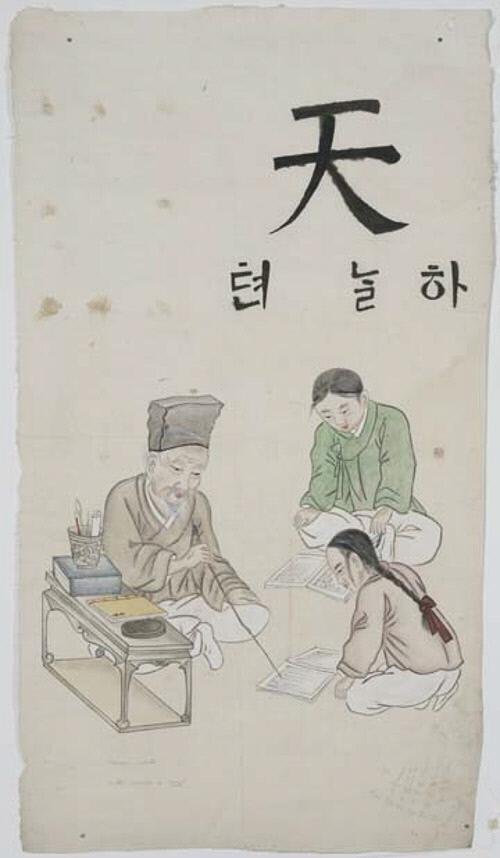

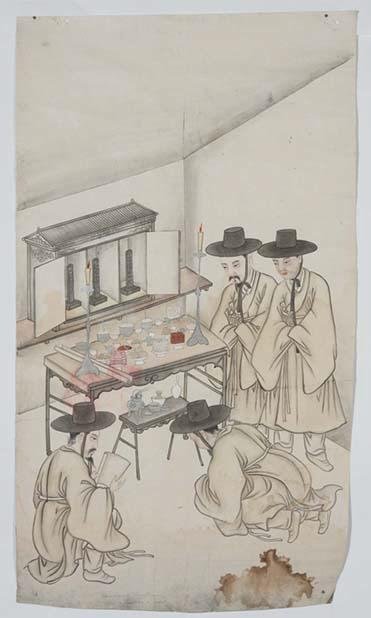

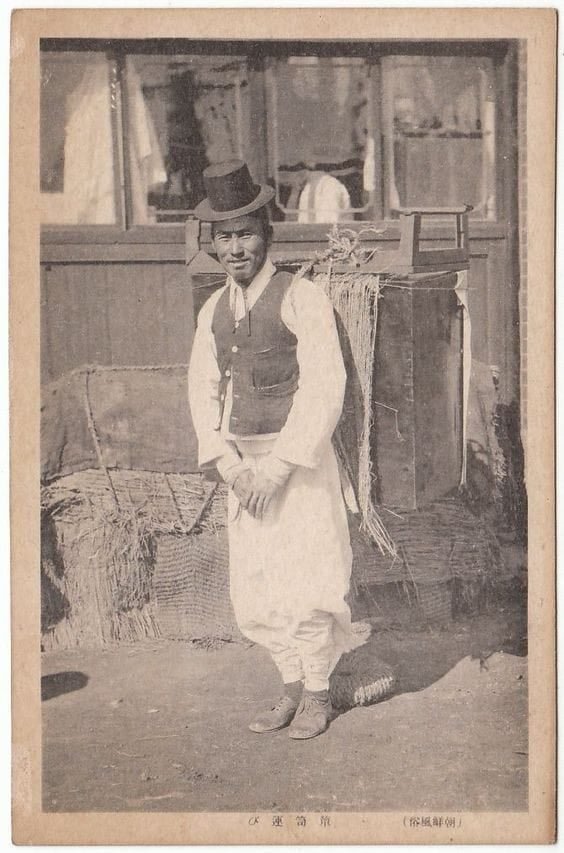

Before the 19th century, paintings provide some insight into the lifestyle of Koreans during the Joseon Dynasty. Starting in the mid-19th century, photographs taken by explorers and early missions become particularly valuable for the same reasons. Here are some illustrations from the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada.

The earliest paintings with Korean furniture we found were done by Shin Yun-bok, better known by his pen name Hyewon (1758–1813), was a Korean painter of the Joseon dynasty. Like his contemporaries Danwon and Geungjae, he is known for his realistic depictions of daily life in his time.

Jusageobae, meaning, “raising a glass at a bar,” is a painting that depicts the scene of a tavern in Hanyang

The photos above indicate that the small low tables called Soban (Photo on the right), the Jang or multi-level clothing cabinet, the rice chest (Photo on the left), existed already in the 18th century.

Ink and light color on paper

Date: 19th century AD

Period: Joseon Dynasty

Dimensions: 62 × 37.8 cm

Ink and color on paper

Date: 1885 – 1910 AD

Period: Joseon Dynasty

Dimension: 124.8 × 70.5 cm

Ink and color on paper

Date: 1885 – 1910 AD

Period: Joseon Dynasty

Dimension: 124 × 69.3 cm

Ink and color on paper

Date: 1885 – 1910 AD

Period: Joseon Dynasty

Dimension: 123.2 × 68.5 cm

Ink and color on paper.

Date: 1885 – 1910 AD

Period: Joseon Dynasty

Dimension: 120.6 × 68.5 cm.

Ink and color on paper

Date: 1885 – 1910 AD

Period: Joseon Dynasty

Dimension: 123.1 × 67.3 cm

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE TRADE.

In “Imwon-gyeongje-ji,” published in the early 19th century, 1108 markets in the country’s eight provinces are named. Among them, 164 markets are mentioned with lists of the goods they dealt in, including more than 80 markets that carried woodenware products.

However, it wasn’t until the late 19th century that the first real foreign visitors were able to access its markets.

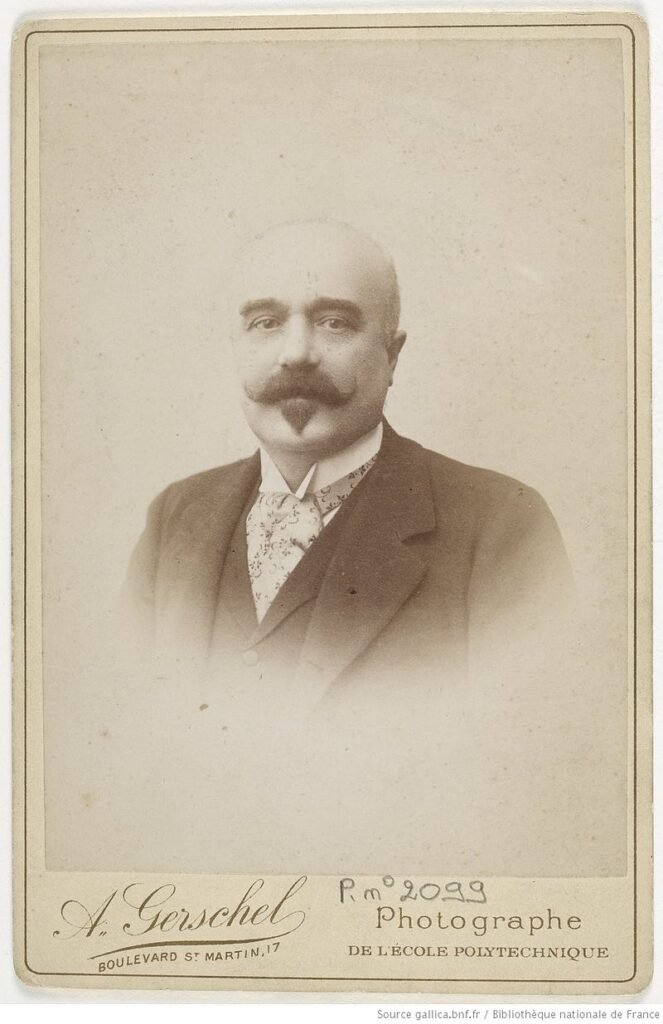

As previously mentioned, few pieces dating before the 18th century are available today. This can be explained by Korea’s turbulent history during the Joseon dynasty, marked by successive wars and invasions, as well as the country’s deliberate isolation. Among the early explorers at the end of the 19th century, Charles Varat, who was instrumental in acquiring the Korean collection exhibited at the Guimet Museum in Paris, reveals his observations in his journal.

In 1888, two years after the normalization of relations between Korea and France, Charles Varat decided to travel to Korea. He arrived less than a year after the arrival of Collin de Plancy, the first French representative to the Yi dynasty.

“Everywhere in Europe, America, Japan, and even in China, I was told that Korea is a mediocre country from an ethnographic point of view,” he wrote in his travelogue. “Indeed, at first glance, there is nothing sadder, nothing poorer than any Korean city, even the capital,” Varat explained the reasons behind this situation.

“Due to long wars and successive invasions of their country, the kings of Korea, in order to prevent the coveting of their powerful neighbors, not only prohibited the entry of all foreigners into their kingdom and the exit of their own subjects but even forbade the exploitation of mines, and enacted sumptuary laws that unfortunately halted national production, previously so brilliant, by leading individuals to conceal their own wealth. Hence arises a state of apparent decay that has deceived many people. But if one takes the trouble to lift the veils, how many curious observations present themselves to you“.

At the same time, other explorers, mostly Anglo-Saxons, took advantage of the opening of the “Hermit Kingdom” to visit the area.

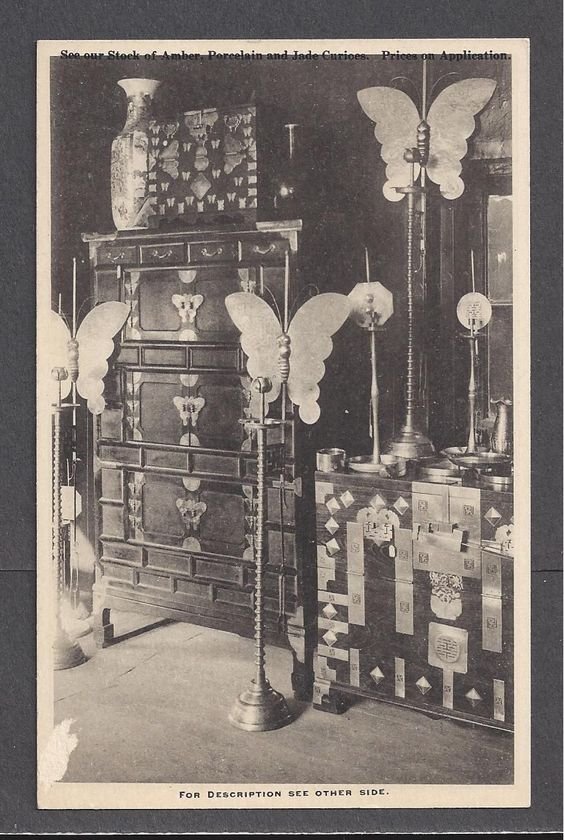

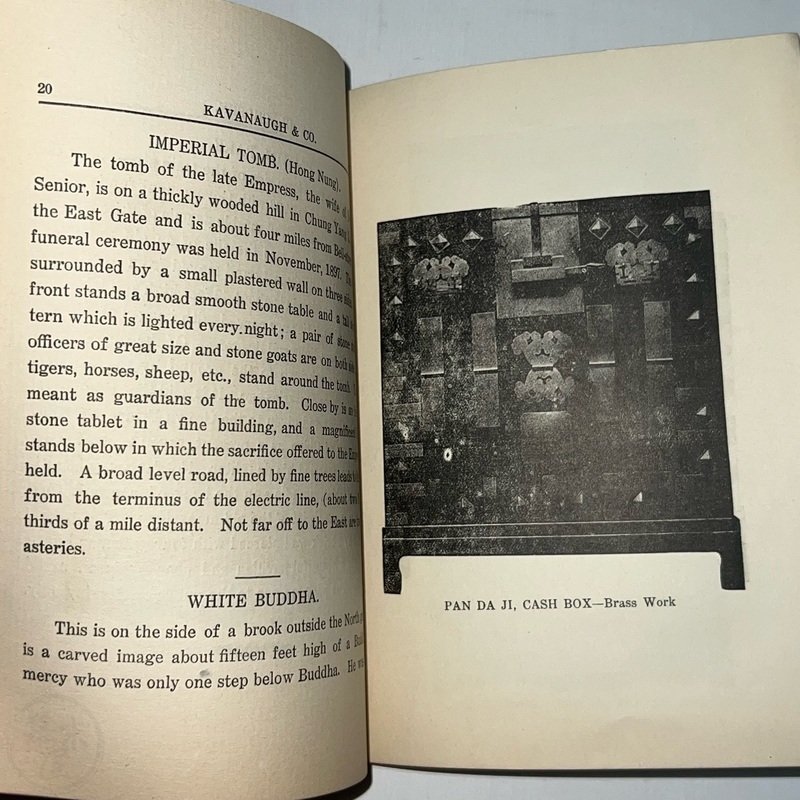

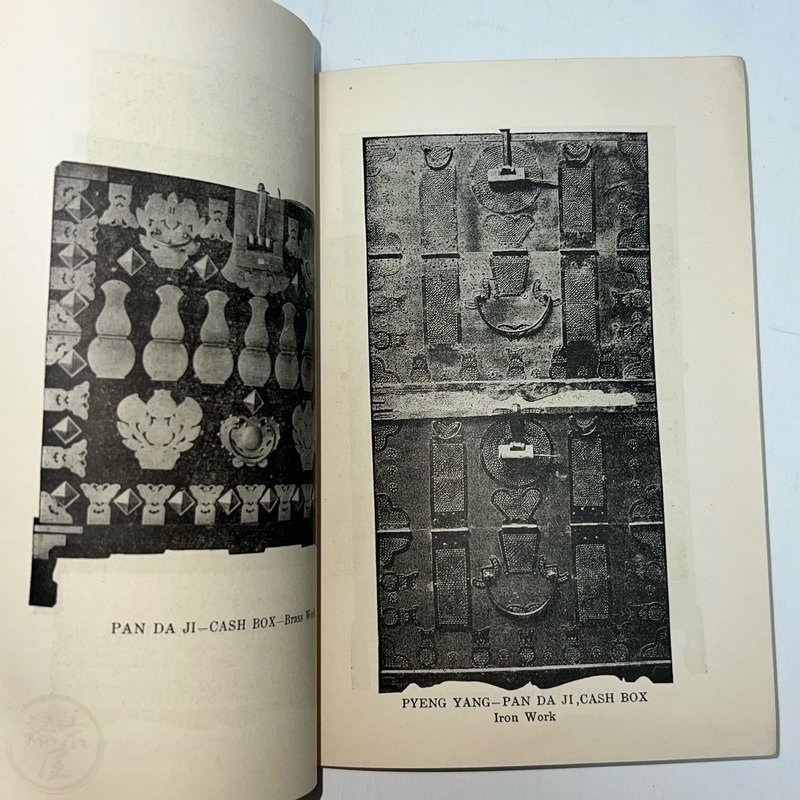

Furniture appears to have been a popular item among both foreign collectors. The “bandaji,” which had the added merit of being large and featuring ornamental elements, was one of the most sought-after pieces of furniture.

The fact that George William Gilmore illustrated one in his book “Korea from its Capital” (1892) reveals the increased demand for furniture and the emergence of ‘Cabinet Street.’ An example of a chest in his possession featured beautifully patterned wood and matching brass designs of butterflies, suggesting that foreigners preferred this type of storage furniture. The photograph of the interior of Gordon Paddock’s house, or the American Legation in Seoul, circa 1904, shows many of the curios that would have been circulated by dealers at the time.

A newspaper article in Kwŏnŏpsinmun on 16 March 1913 reported this increasing demand from Western travelers, titled “ Korean Cabinets are exported to the West “. It reads: Recently, Korean clothing cabinets have been remarkably exported to Europe and America. In the past Westerners used to buy fans, brassware, and other utensils, but recently the clothing cabinets have become very popular. They cost 14-15 wŏn and more, some reaching 100 wŏn each.

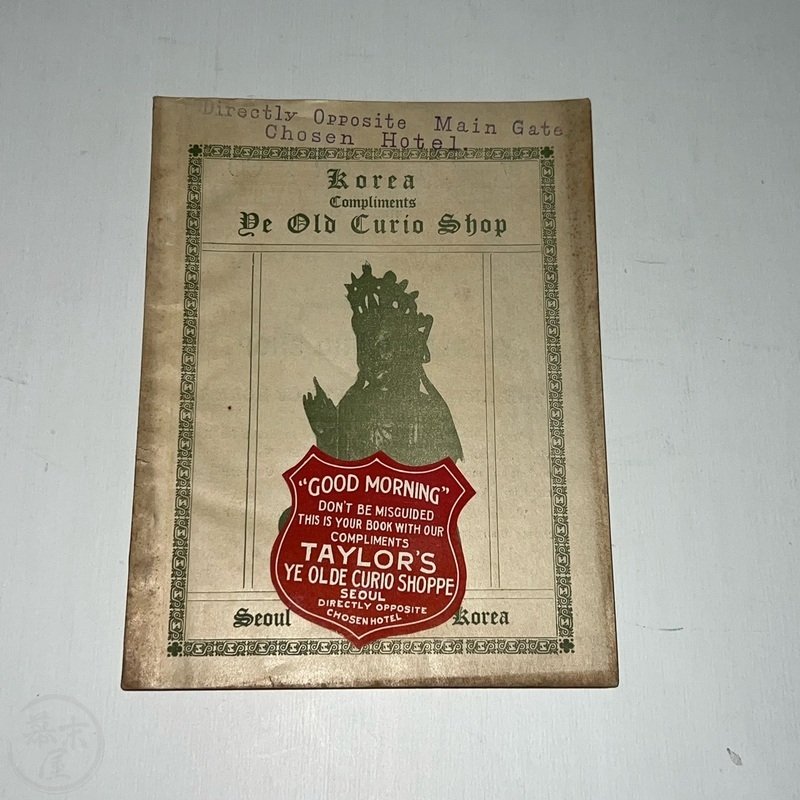

A catalog from “Taylor’s Ye Olde Curio” shop, published around 1917, allows us to explore the furniture pieces available at that time.

(London: Thomas Cook & Son, 1917)

It is interesting to note that there are few bandaji, nong, or coin chests, but instead, small cabinets with large doors and a fairly contemporary design for the time.

This reflects that at the beginning of the 20th century, the new market in Korea, primarily intended for Westerners, played a significant role in boosting the production of furniture. Some of the designs were even modified to cater to the preferences of this new clientele.

It is now clear why so few original pieces exist today. Among the oldest, many of them available on the market were acquired during missions to Korea in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

NOTE: These pieces serve as a good example of the furniture that was in vogue in Korea in the early 20th century when the first foreign merchants began trading. The furniture often featured numerous brass hinges. Note the construction of the back part, which typically followed a European style.

(PHOTO ABOVE): Korean cabinet Mori-Jang. around 1900.

Rectangular body on curved feet under a curved frame. At the front wing doors, five drawers in different sizes and blind cassettes. Handles in the shape of Ruyi, decorated with brass appliqués in the shape of rosettes and bats. H. 109cm, W. 122cm, D. 51 cm.

PROVENANCE: Private collection of a shipping clerk at Nord Deutscher Lloyd, who was employed in East Asia business in Shanghai and Yokohama until 1940.

Another similar piece. Early 20th century. Small cabinet with two upper drawers, double doors providing access to eight additional drawers, and a lower compartment closed by doors.

Wonderful images with information on an old piece which I had found…morijang!

Glad you liked it.