소목 (Somok), traditional joinery.

During the Joseon Period, a wide range of joining techniques was employed. While Korea’s climate, characterized by four distinct seasons, facilitated the availability of exquisite woods, it also led to significant wood movement, resulting in warping and cracking of wood panels.

A piece of furniture typically comprised three main components: the top, body, and legs. The first joining method involved connecting smaller pieces to create larger ones, while the other method focused on fitting pieces together for structural integrity. The wood’s natural characteristics and decorative grain patterns were taken into consideration. In ancient times, Joseon carpenters consistently avoided the use of nails and glue. Instead, they used small bamboo sticks to reinforce butt joints on drawers.

MAIN JOINING TECHNIQUES.

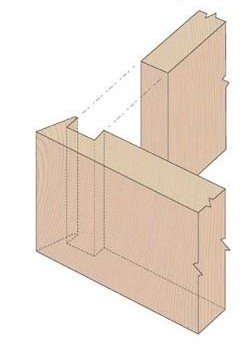

YONGUITCHA IM – 연귀짜임 – MITER JOINT

A miter joint is created by cutting two pieces of wood at a 45-degree angle, which are then joined together to form a corner with a 90-degree angle.

In Korean furniture, this type of joint was commonly used in constructing frames, particularly in building the front of Jangs. It was also employed in chest body construction to connect legs to frames in kitchen furniture.

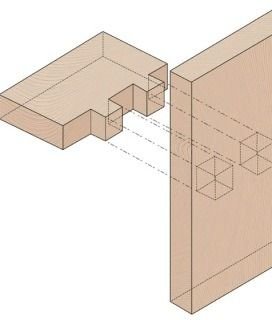

T’OKTCHA IM – 턱짜임 – LAP JOINT also known as RABBETED JOINT.

A lap joint was utilized for joining two pieces of wood by overlapping them.

These joints are quick and easy to create and offer reasonable strength due to the extensive gluing surface provided by the long grain-to-long grain connection.

The shoulders of the joint also offer some resistance to racking. In some cases, they can be further reinforced with dowels or mechanical fasteners to enhance their resistance to twisting.

CHANGBUCH OKTCHA IM – 장부짜임 –MORTISE AND TENON JOINT

Simple and sturdy, the mortise and tenon joint was commonly employed to join two pieces of wood, often at an angle close to 90 degrees.

While there are numerous variations of this joint, the fundamental concept involves inserting the end of one member into a hole cut in the other member.

The end of the first member is referred to as the tenon, and it is typically narrower compared to the rest of the piece.

The hole in the second member is known as the mortise.

SAGAEION KUIPAN CHA IM – 연귀짜임 – DOVETAIL JOINT

A dovetail joint is an aesthetically pleasing joinery technique. It is renowned for its exceptional resistance to being pulled apart, and it is frequently employed to join the sides of a box.

A sequence of pins, cut to extend from the end of one board, interlocks with a series of tails cut into the end of another board. Both the pins and tails have a trapezoidal shape. Once glued, the joint becomes permanent and does not necessitate any mechanical fasteners.

Dovetail joints are commonly used in box construction, such as in the making of bandaji.

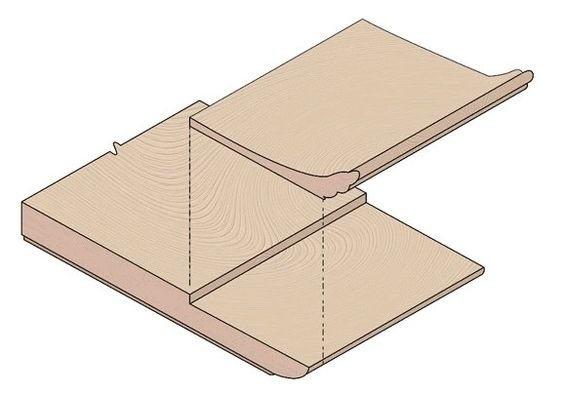

MATCHA IM – 맞짜임 – BUTT JOINT –

A butt joint occurs when two pieces of wood are joined by simply butting them together.

The butt joint is the simplest type of joint, but it is also the weakest because it relies on small wooden pins or other forms of reinforcement to hold it together.

Butt joints have been commonly utilized in drawer construction.

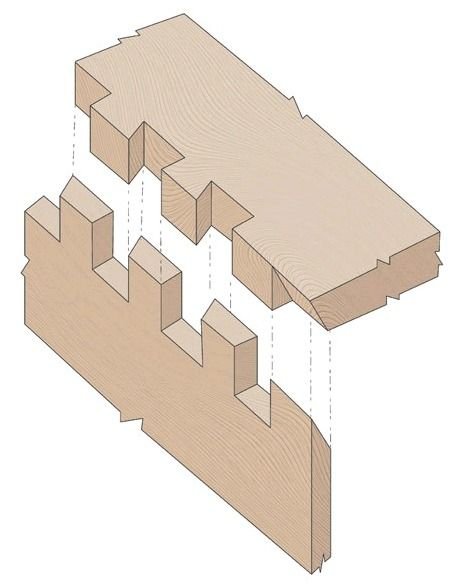

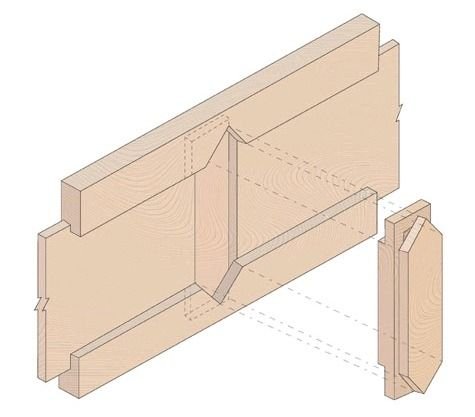

SAGAETCHA IM – 사개짜임 – FINGER JOINT

A finger joint was employed to join two pieces of wood at right angles to each other.

It is akin to a dovetail joint, with the distinction that the wooden pins are cut square rather than at an angle.

This joint technique requires the use of glue to hold it together, as it lacks the mechanical strength of a dovetail joint.

Similar to the dovetail joint, this type of joint was frequently used in Bandaji construction to assemble the large panels used in the chest body.

CONSTRUCTION METHODS.

TOP JOINERY

There are three main types of top construction:

- Overhanging board or “Kaep-an” structure, in which the top panel is larger than the body of the chest. This construction was commonly found on book storage chests, stationary chests, and safes. The single board was attached to the body using a mortise and tenon joint.

- Overhanging frame and panel construction, which was common on Jangs, head side chests, and kitchen chests. Panels were fitted into the frame using a lap joint, while the bars of the chest body were joined to the frame by a miter joint.

- Simple box with no overhanging top, as seen in most Bandaji, Nong, and wedding box constructions. Various joinery methods could be used, including miter joints, lap joints, dovetail joints, finger joints, and mortise and tenon joints.

SIDE PANEL JOINERY

Side panels were connected using half-lap joints. Small metal hinges were wrapped around the corners to enhance strength.

For Bandaji, where thick wooden boards were employed, the side panels were typically joined using finger or dovetail joints.

DOOR JOINERY

Doors on Jangs and Nongs typically featured frames with inset panels. Frames were connected using miter joints, while the door panels were set within the door frame using lap joints.

These door panels were often constructed from a thin slice of precious wood (such as cherry, zelkova, or ash) backed by wood with less decorative grain, like pine or paulownia, in order to reduce the likelihood of cracking.

FRONT PANELS

Molding bars were employed to separate the front panels on a chest. Horizontal rails were connected at the corners using miter and lap joints.

Frame and panel construction was utilized in crafting doors and other decorative front features for clothing chests. This technique involves inserting a floating panel within a frame.

Typically, the panel is not glued to the frame; it is allowed to float within it to accommodate the seasonal movement of the wood, preventing any distortion of the frame.

LEG STRUCTURE

The stands were used to raise the chest above the heated floor (Ondol). Leg stands were sometimes detached from the frames of the chest, especially in the case of Nongs, to facilitate transportation.

The Cabriole style was the most commonly used, and it was inspired by Chinese design. The bottom frame on the legs was important for both structural reasons and protection. This technique was employed by the Chinese at a very early stage.

Bandaji chests always had two thick boards underneath to elevate them off the floor. The legs on North Korean Sun Sun I bandaji could be more elaborate, often featuring designs on the front part.

Kim Sam-Jae. 2018/01/22. 168 pages.

ISBN: 978-89-97252-22-0

How can I purchase the Book mentioned above and do you have instructional workshops for training.

Dear John,

This book has been published in Korea. I do not know if an english version exist. Please check the following link: https://nontili.co.kr/product/%ED%95%9C%EA%B5%AD%EC%A0%84%ED%86%B5%EA%B3%B5%EC%98%88-%EC%9A%B0%EB%A6%AC%EA%B3%B5%EC%98%88-%EB%94%94%EC%9E%90%EC%9D%B8-%EB%A6%AC%EC%86%8C%EC%8A%A4%EB%B6%81-03-%ED%95%9C%EB%88%88%EC%97%90-%EB%B3%B4%EB%8A%94-%EC%86%8C%EB%AA%A9/1110/ . No special workshop.

Where can I find contract joineries that still do traditional Korean hanji paper doors and screens?

Where are you located?