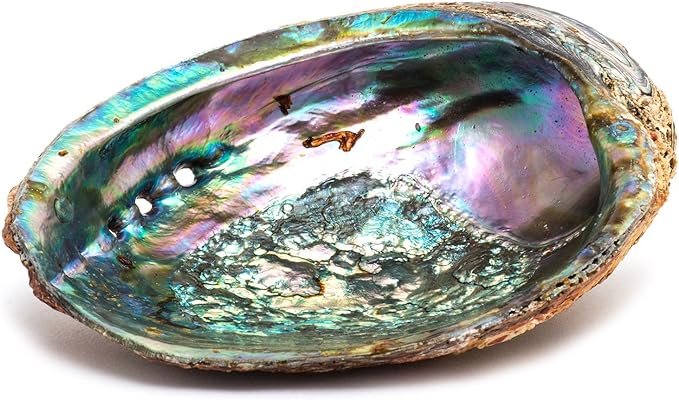

Mother-of-pearl, also known as nacre, is an inorganic composite material produced by certain mollusks as an inner shell layer, and accumulated in other shells, such as freshwater pearl mussels, in the form of pearls. It is very strong, resilient, and iridescent. It can be found in strains of mollusks in the class of “Bivalvia“, such as the clam, oyster, or mussel; “Gastropoda“, such as snails or slugs; and “Cephalopoda“, such as cuttlefish or squid. At current, pearl oysters, freshwater pearl mussels, and to a lesser extent, abalones are predominant sources of mother-of-pearl material.

The mother-of-pearl material used in traditional inlay crafts is mainly that of abalone. Though artisans do also use the mother-of-pearl of other shell-fish, they believe the abalone is of the highest quality, producing the most beautiful colors and light reflections.

Mother-of-pearl can be adhered onto many different kinds of materials such as wood, porcelain, metal, and thick paper. There are three main methods of attaching the mother-of-pearl, the first of which is to carve the surface of the base material exactly to the shape of the mother-of-pearl motif and inlay it. The second method is to glue the sheet of mother-of-pearl directly onto the surface. Lastly, one can process the mother-of-pearl into miniscule pieces and scatter them onto a glue-applied surface.

The origins of mother-of-pearl are not clear but it is known that the crafts enjoyed huge popularity in China during the Tang Dynasty (618~907). Most of the wood and mother-of-pearl shells at the time were sourced in South Each Asia, which may lead us to believe that the origins of the craft also lie in South East Asia. During the Ming (1368~1644) and Qing (1616~1912) Dynasties, the methods of applying metals, gold, or some other materials to the back of mother-of-pearl sheets so that one could see the beauty through the almost translucent sheets of mother-of-pearl after applying them onto the surface of wood crafts developed and reached their peak in China.

In Korea, lacquerware with mother-of-pearl inlay is referred to as “najeon chilgi“. The term “najeon” is composed of the character “na“, signifying shell, and “jeon“, denoting decorative techniques, while “Chilgi” is the term used for lacquering.

Korea’s “najeon-chilgi”, mother-of-pearl inlay methods, are known to have been passed down from China’s Tang (618~907) Dynasty to Shilla (57BC~935AD); a country located in the south-eastern part of Korean peninsula) during the time of the Three Kingdoms. Following on from the Tang Dynasty, this craftsmanship deteriorated in China during the Song Dynasty. On the other hand, in Korea during the Goryeo (918~1392) period, mother-of-pearl craftsmanship developed and spread extensively leading to mother-of-pearl inlay crafts and ceramics becoming representative of the Goryeo period.

The “najeon-chilgi” of Goryeo are highly valued black lacquered mother-of-pearl crafts adorned with images such as chrysanthemums and vines. Such crafts of the Goryeo Dynasty, while hugely popular at the time, deteriorated with the falling of the Goryeo Dynasty. Towards the end of the 13th century and into the Joseon Dynasty period (1392~1910), such crafts underwent stark transformations.

12th century

Lacquered wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl

H: 4,5cm. x Diam.: 12,4cm.

Taima-dera Temple.

“Najeon-chilgi” of the Joseon Dynasty can be categorized into 3 broad groups.

- Images of lotus flowers and peonies, a pair of phoenix, a pair of dragons, or “Bosanghwa”, an imaginary flower resembling the lotus, were among the common motifs appearing on mother-of-pearl crafts of 16th century pre-mid Joseon Dynasty. These patterns were noticeably simpler and larger in scale than those of the Goryeo period.

- During the late Joseon Dynasty period (1700~1800), mother-of-pearl designs became more free, with images of peony blossoms and bamboo, or flowers and birds appearing frequently. Many mother-of-pearl images of this time portray realistic representations of the “Ten symbols of Longevity” (sun, mountain, water, rock, pine tree, moon, boolocho, turtle, crane, and deer), and other natural objects. At the same time, peony blossoms, bamboo, flowers, and birds started being portrayed in humorous and childish ways, leading to another unique and simple dimension to the beauty of Najeon from the Joseon period.

- Following on from the Joseon period, Korea entered a period of Japanese colonization (1910~1945), during which mother-of-pearl craftsmanship was only barely able to survive. Restoration of Korea’s independence in 1945 re-opened doors for this craft.

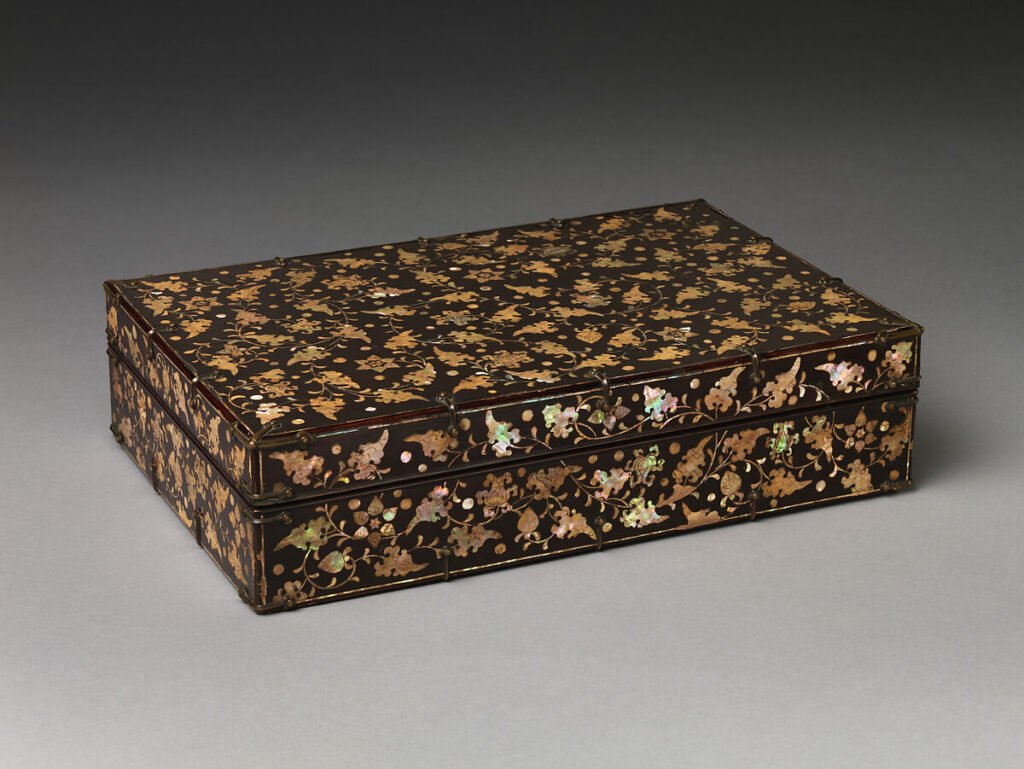

H. 9,2cm. W. 24,1cm, D. 36,5cm.

Scholarly men collected and used stationery boxes like this to hold paper and writing implements. A rare example of early Joseon lacquer, the box’s ornate design of peony blossoms and acanthus-like leaves illustrates the expansion of sophisticated Goryeo-dynasty techniques and traditions. Peony blossoms of similar form can be found on inlaid buncheong ware; the stylized acanthus-like leaves are distinctive to this example and to the few other extant boxes of its type, which are nearly identical. Collection: The Met, New York.

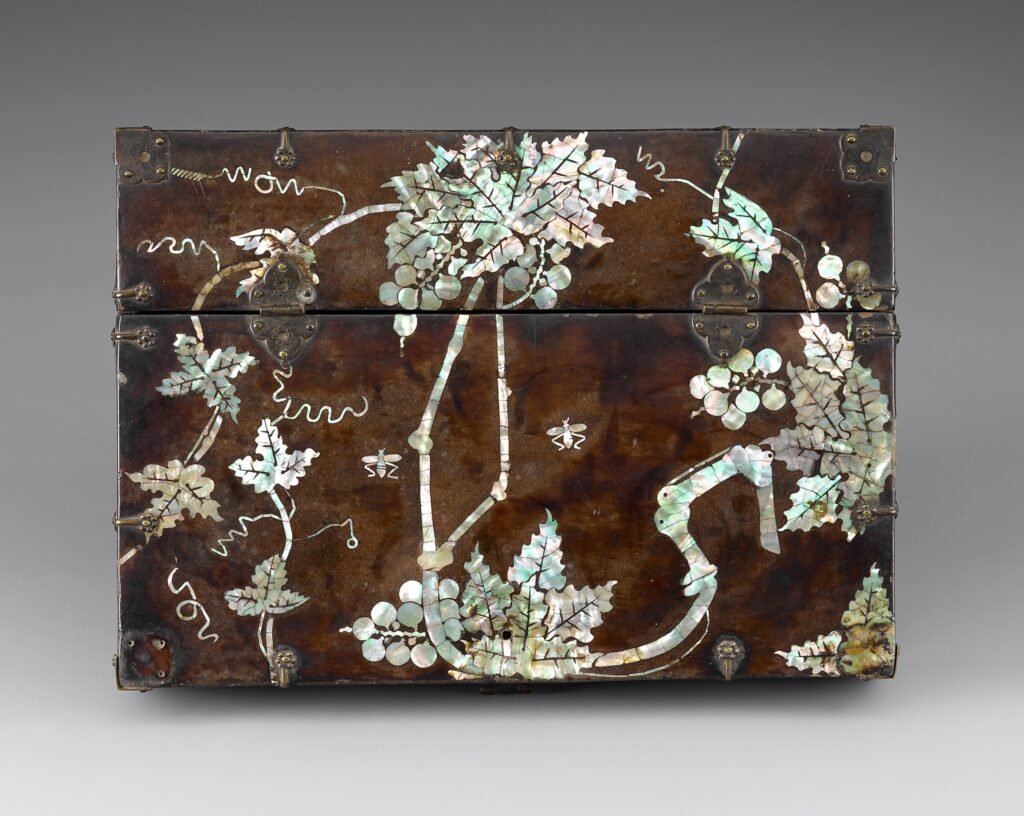

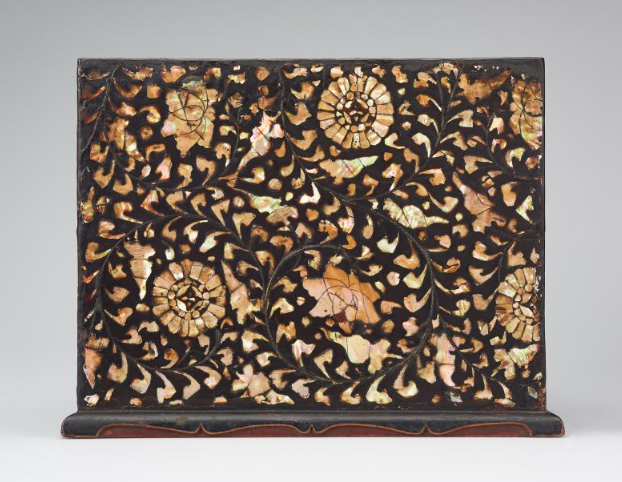

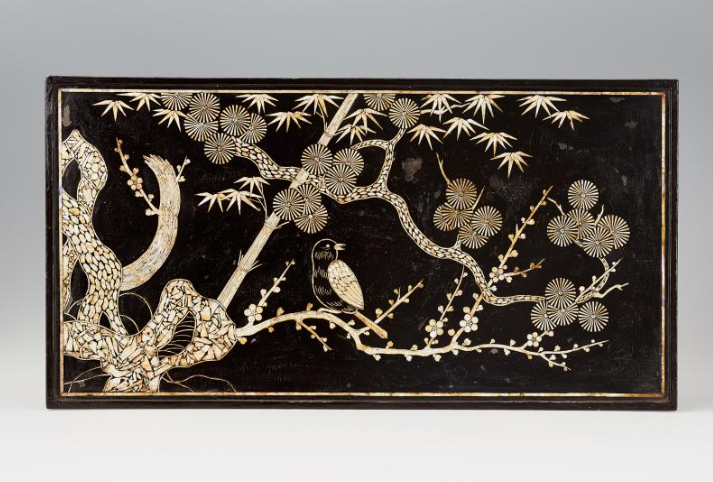

H. 18.8cm, 83.5×52.6cm.

Chrysanthemum arabesque design.

Late Goryeo to early Joseon period.

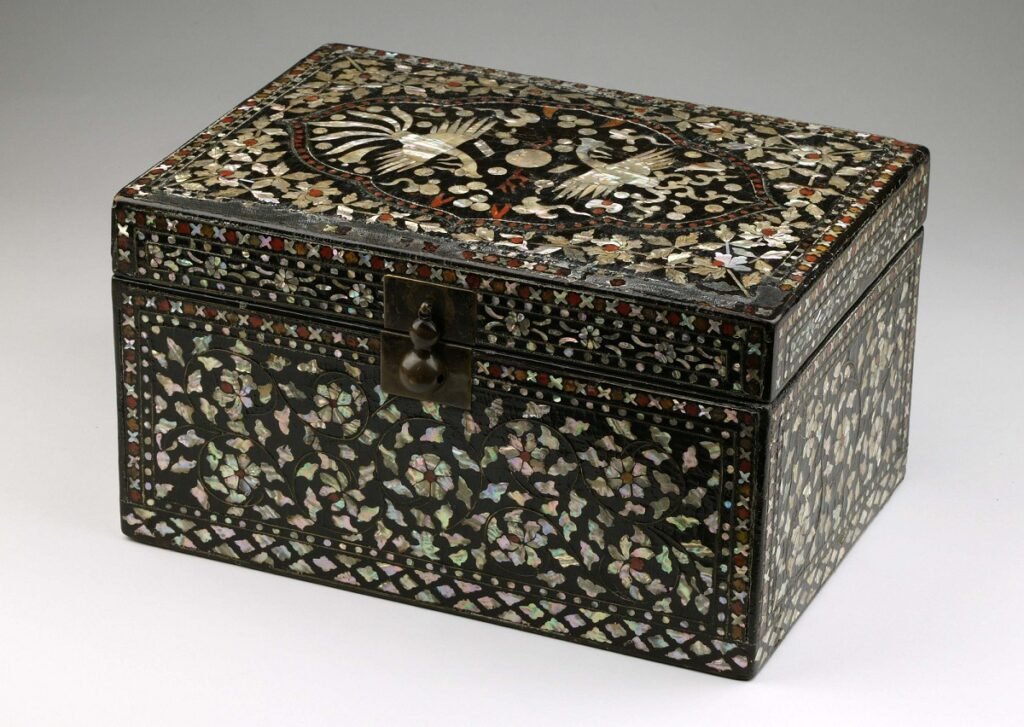

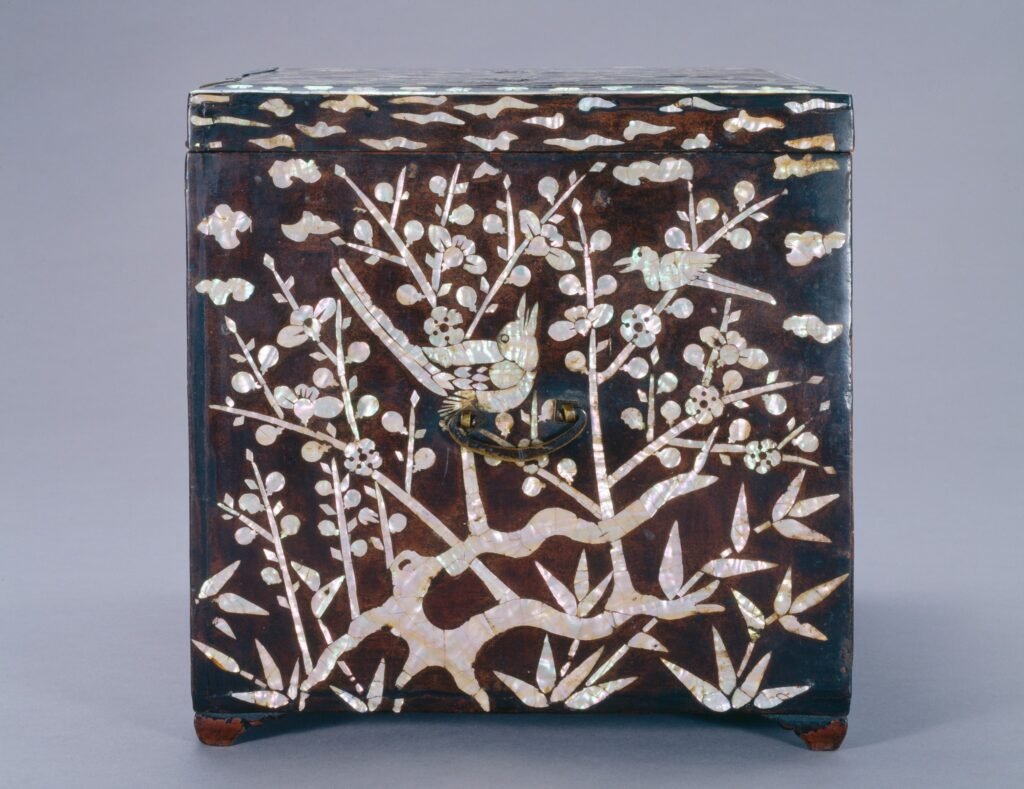

H. 11,5cm, W. 17cm, D. 9cm.

Small box with rounded shape and intricate floral arabesque patterns. The pattern are created using mother-of-pearl inlay. It was probably used by an aristocratic woman in the Goryeo dynasty to store her cosmetics.

Collection: The Museum Yamato Bunkakan. Japan.

Collection: The Met New York.

H. 18cm, W. 46,1cm, D. 31,3cm, Collection: National Museum of Korea. (3 photos).

H. 21.8cm, L. 90.5cm, W. 55.8cm.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Germany.

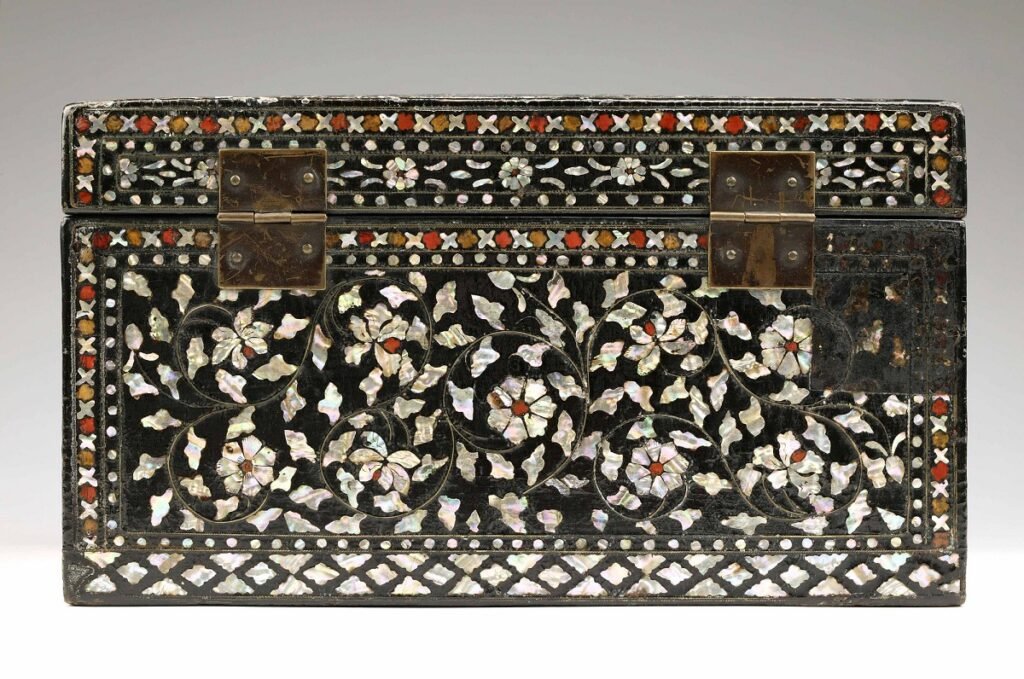

Lacquer on wood with inlaid mother-of-pearl and metal wire, and metal fittings. Date1700-1800.

H. 17 cm x W. 16 cm x D. 13.5 cm.

This box is from the Joseon dynasty, featuring chrysanthemums as the main decorative motif. In Joseon-dynasty craftsmanship, mother-of-pearl is predominantly used as the design material, with most areas within the flowers and leaves solely inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Metal wire was limited to the branches. Compared to Goryeo lacquerware, Joseon lacquerware motifs became sparser, more naturalistic, and surrounded by negative space. Joseon artisans emphasized highlighting the distinctive characteristics of the raw material, mother-of-pearl. Collection: Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, USA.

Lacquered Comb Box Inlaid with Mother-of-Pearl, Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897). Collection: National Museum of Korea.

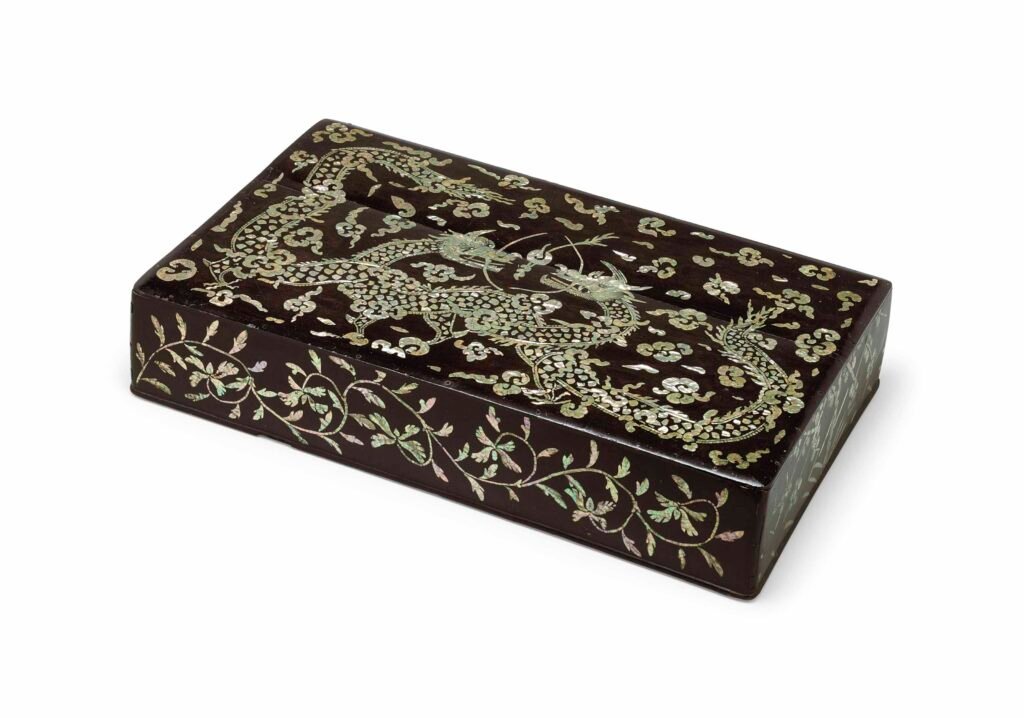

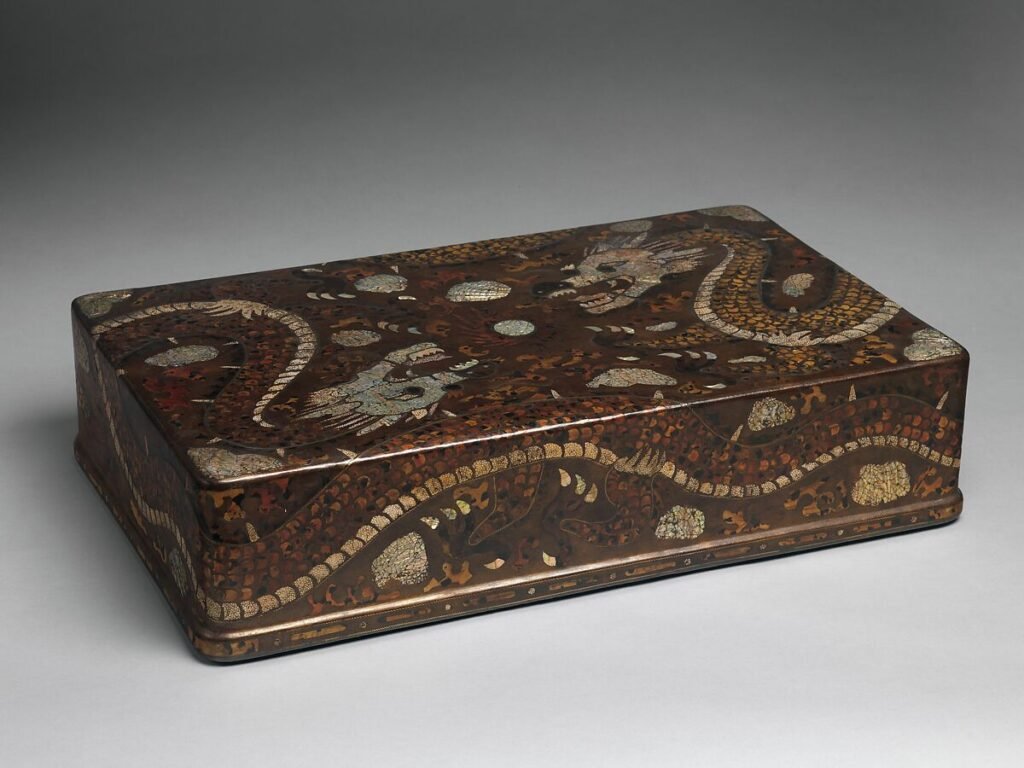

Joseon dynasty (early 20th century)

Rectangular, with rounded corners elaborately inlaid on the overhanging lid in large pieces of mother-of-pearl with two confronted dragons facing off on either side of a flaming jewel with a backdrop of scalloped clouds, the sides of the lid inlaid in mother-of-pearl with lotus arabesques on the long sides, inlaid with bamboo on one short side and inlaid with plum branches on the opposite short side, the ground of the lid black lacquer, which is repeated on the plain lower box; interior lined with green paper

28½ x 17 5/8 x 5¼in. (72.6 x 44.8 x 13.3cm.) Christie’s Auction.

H. 17,1cm, W. 73cm, D. 45,1cm.

This box’s lively design features two dragons chasing a flaming jewel. The beasts’ long, sinewy bodies wrap around the sides of the box; their heads face each other at opposite corners at the top. The masterful mixture of diverse materials—mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, and ray skin—highlights different textures, emphasizing not only the tactile quality of the mythical beasts but also their dynamic character. Collection: The Met, New York.

H. 22,7cm, W. 20,5cm, D. 34cm. Collection: Busan Metropolitan City Museum.

Collection: Busan Metropolitan City Museum

Collection: Busan Metropolitan City Museum

Lacquered wood with inlaid mother-of-pearl.

H. 11 cm x W. 49.1 cm x D. 26 cm.

Dynasty: Joseon dynasty (1392-1910).

Date: 1700-1800

Asian Art Museum collection. San Francisco, USA.

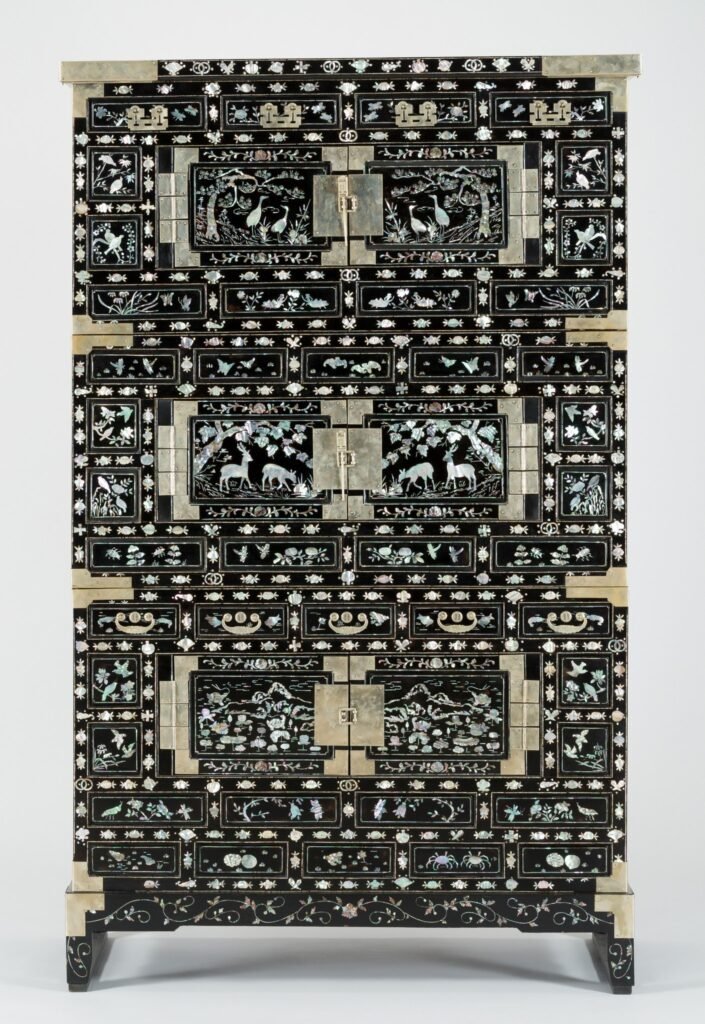

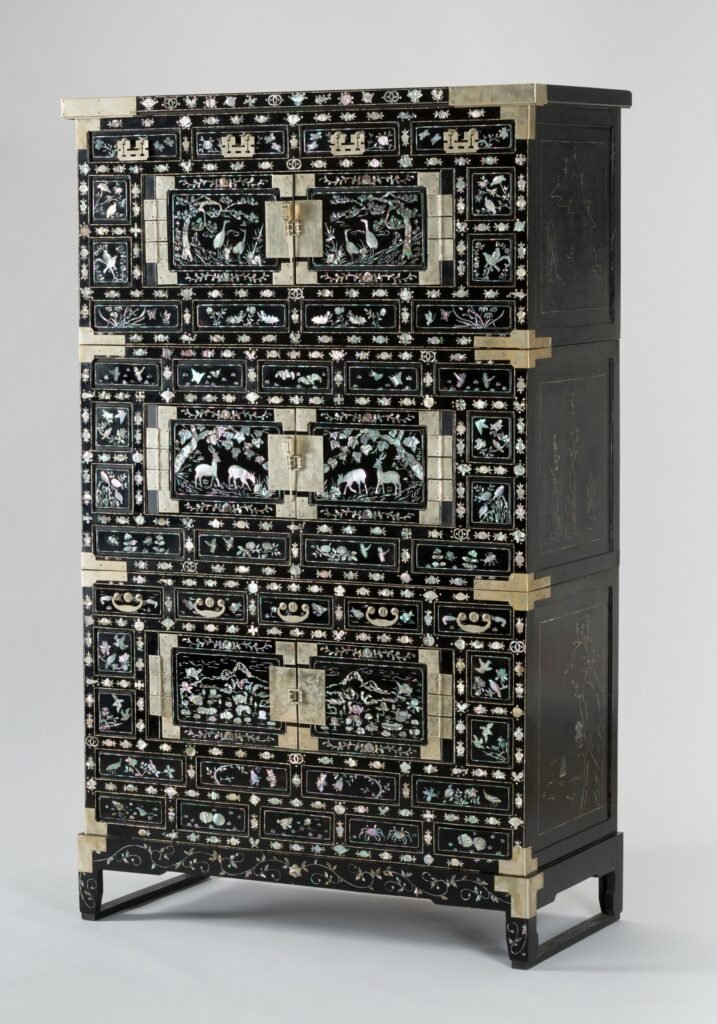

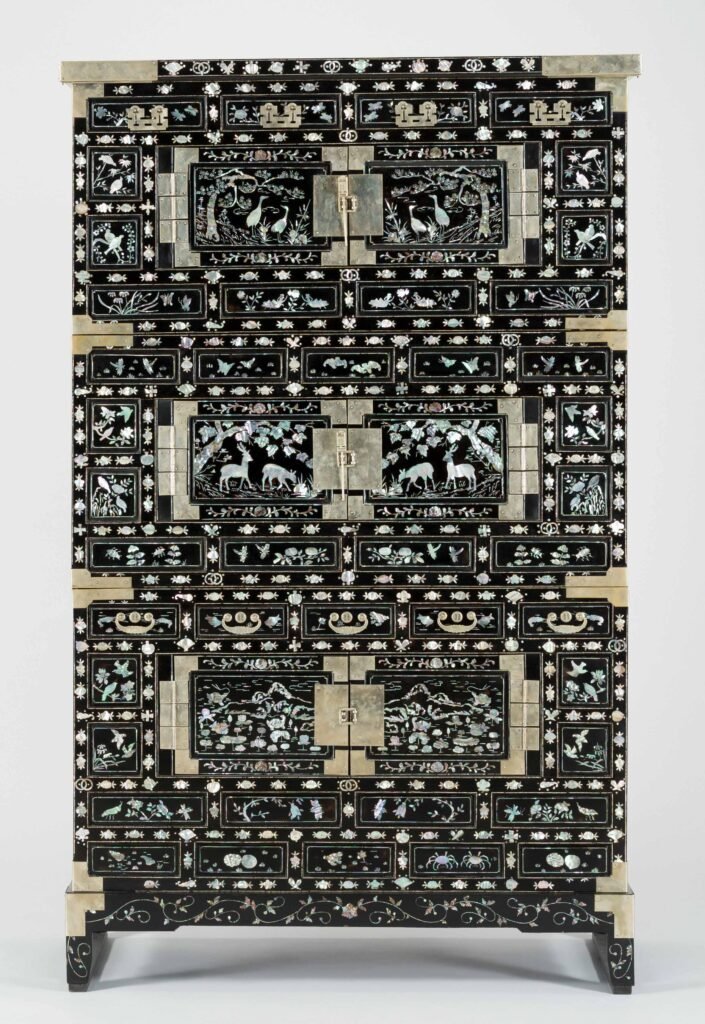

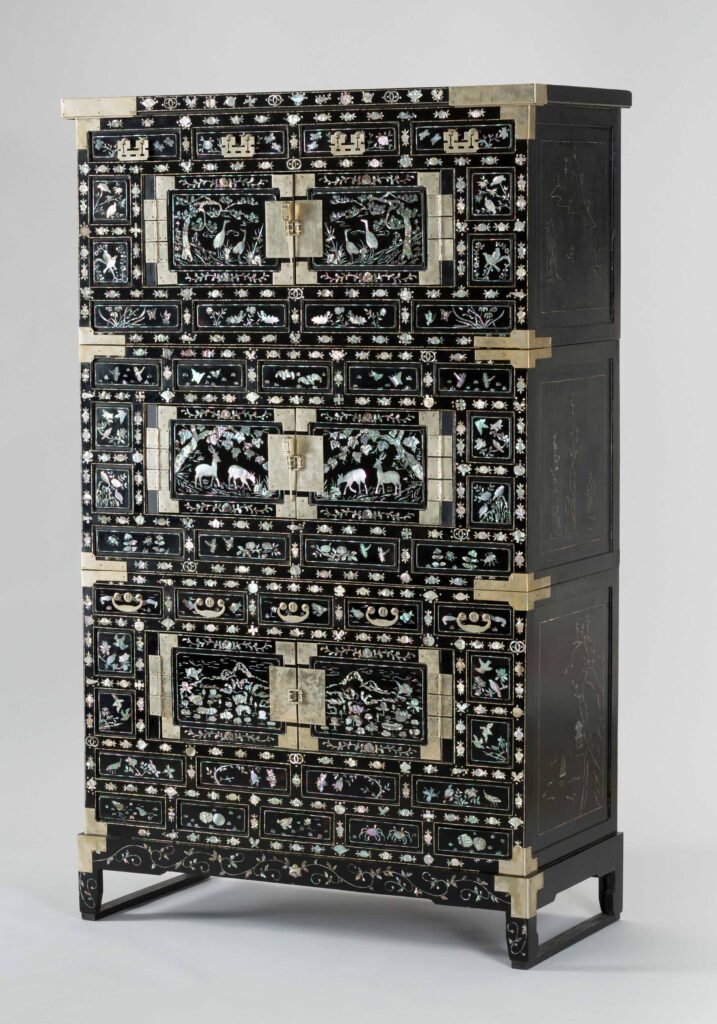

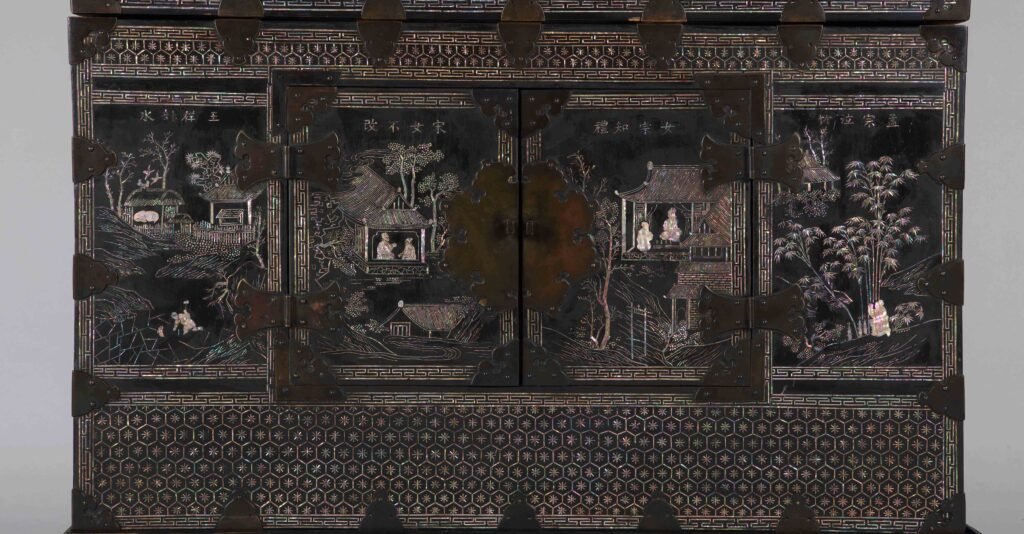

A NORTH KOREAN CHEST (Photos above)

Mother-of-pearl three-story cabinet with ten symbols of longevity pattern, 2006 North Korean crafts.

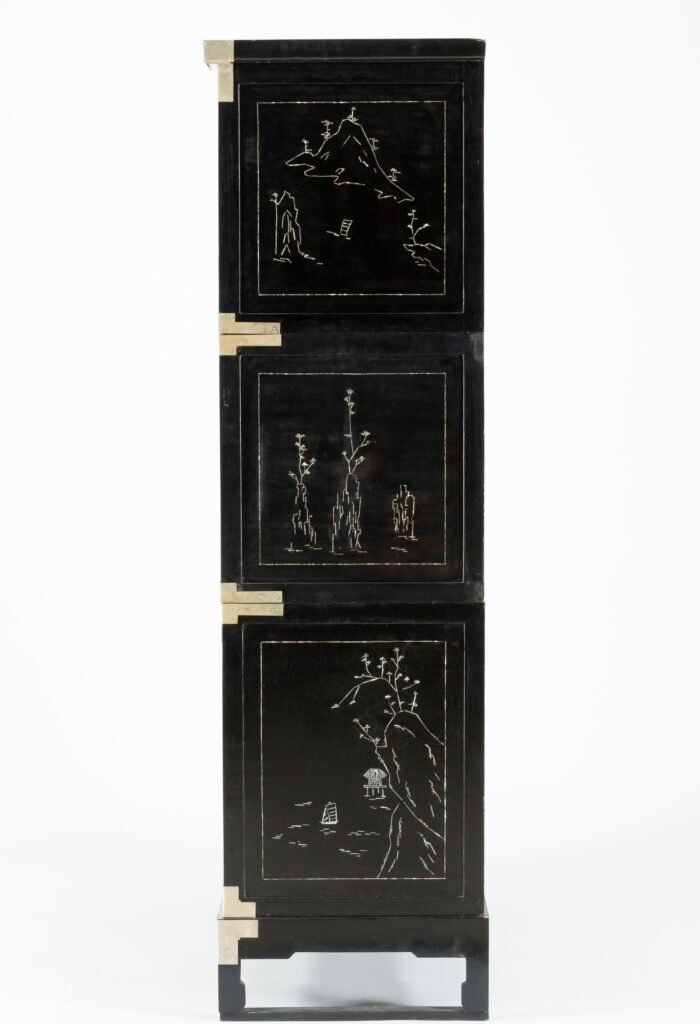

“A rectangular parallelepiped shape features a storage cabinet with a swinging door beneath a rectangular ceiling plate. This three-layer structure has each floor separated, and horse-drawn legs are attached to the lower part, connected by foot straps. The swing doors on each floor are hinged with square hinges, and a square front base is attached. A lock engraved with the letter ‘囍’ is placed on the pear tree in front of the 2nd and 3rd floors. The four corners of each door plate are reinforced with ear decorations. Four drawers with bat-shaped handles are attached to the top of the first-floor door, and a ‘ㄷ’ shaped handle is affixed to the top of the third-floor door. The front four corners of the ceiling plate, gunny sack, and each layer are reinforced with gamjabi. The entire surface and interior are painted with black lacquer, and the front is adorned with the Ten Longevity Symbols, while both sides showcase landscape patterns created using the mother-of-pearl technique—a method in which mother-of-pearl is carved into the patterned part of the tree and then inlaid with mother-of-pearl”.

Written by Seo Geum-ryeol, a professor at Pyongyang Art University in North Korea.

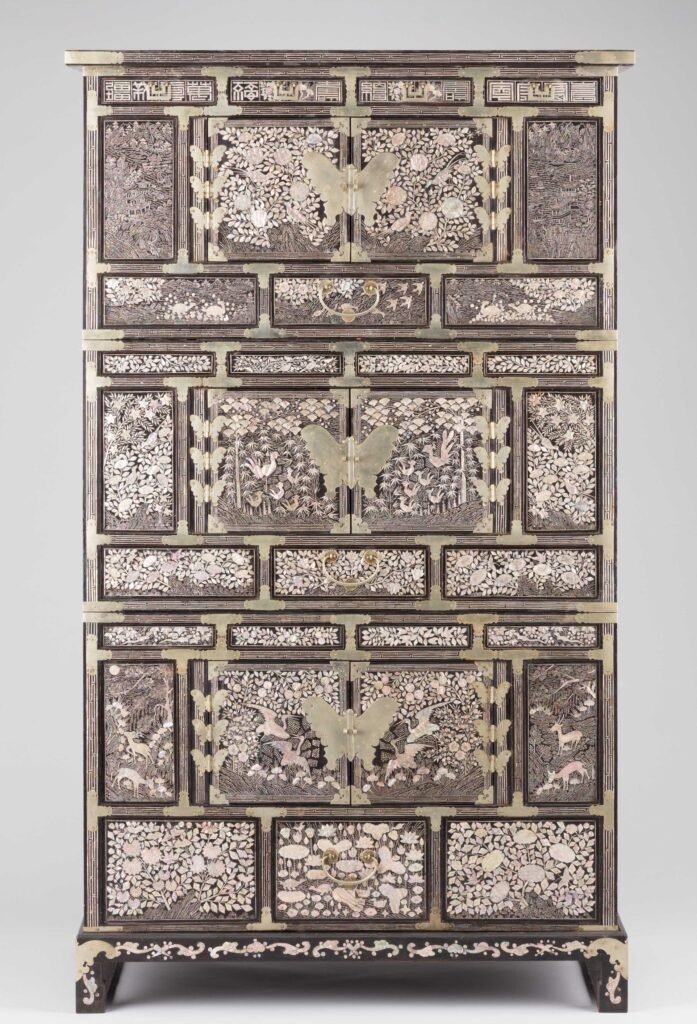

Nong. Japanese occupation period. H. 140cm, W. 77cm, D. 39cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul. 4 photos under.

Three level chest with mother of pearl inlay. Collection National Folk Museum, Seoul. 4 photos under.

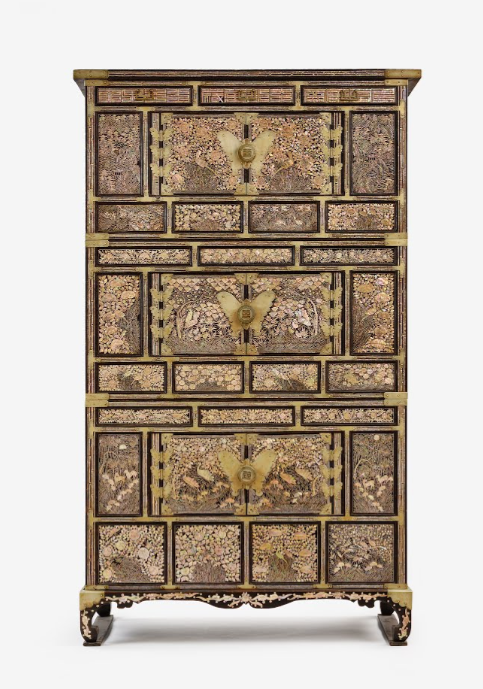

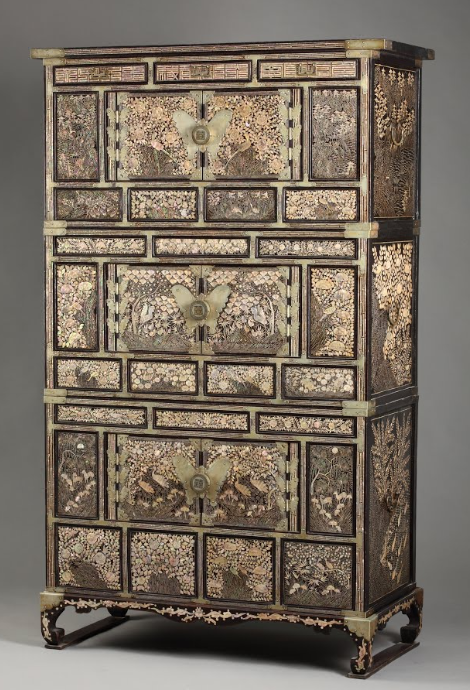

Two level chest. H. 138,5cm, W. 77,2cm, D. 38cm. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul. 3 photos under.

MOTHER-OF-PEARL APPLICATION METHOD.

The following analysis is based on an excellent study conducted by Colleen O’Shea, Mark Fenn, Kathy Z. Gillis, Herant Khanjian, and Michael Schilling, published as “Korean Lacquerware from the Late Joseon Dynasty” by the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

To begin with, each object consists of a wooden or bamboo substrate, a textile layer, a lacquer surface comprising one or more layers, and numerous inlay elements. The inlay materials are used to create designs on the prominent surfaces of the objects and may include mother-of-pearl, ray skin, tortoiseshell, wire, golden-colored flakes, and possibly horn.

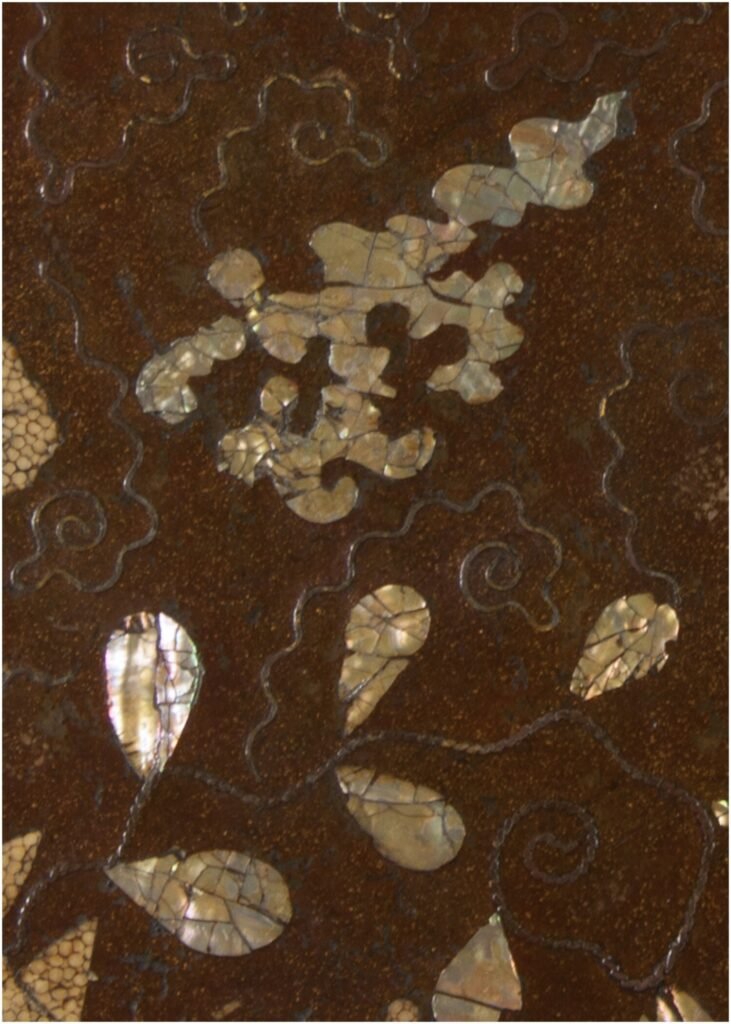

To fashion mother-of-pearl pieces into various shapes, craftspeople from the Goryeo through the Joseon dynasties utilized a range of tools, including knives, chisels, engravers, scissors, awls, needles, and gimlets for piercing holes. In the twentieth century, they began using fretsaws. The cut mother-of-pearl pieces were either applied in their entirety or further refined using the “tachalbeop” technique. In this method, curved pieces of mother-of-pearl were struck with a hammer or a knife to flatten them, resulting in a distinctive cracked texture.

Date: 19th century. Lacquer inlaid with mother-of-pearl and metal wire. H. 38,7cm, W. 42,2cm, D. 30,8cm. The decoration on this table continues the designs of Goryeo-dynasty lacquer. The scroll pattern in wire, delicate three-pointed leaves, and circular geometric pattern are common in the earlier tradition. The scallop framing of the floral motif on the tabletop evokes the shape of ogival trays. Collection: The Met, New York.

Date: 19th century. Lacquer inlaid with mother-of-pearl and metal wire. H. 25,4cm, W. 33,3cm, D. 33,3cm. The decoration on this table is inspired by Goryeo-dynasty design. The wire-inlay scroll pattern, delicate three-pointed leaves, and circular geometric pattern are common Goryeo-lacquer motifs that were carried through in this Joseon lacquer. The scalloped framing of the tabletop’s floral motif evokes the shape of the ogival trays.

Collection: The Met, New York.

The hinged doors and the front of the ‘Nong’ are adorned with an Ajamun (亞字文) pattern running around their perimeters. Each compartment depicts icons representing the Five Principles of Conduct. Starting from the right, the contents and titles of Maengjongeupjuk (孟宗泣竹) and Wang Sangbubing (王祥剖氷) tell the story of a filial son, while Songnyeo Bulgae (宋女不改) and Yeojongjirye (女宗知禮) narrate the story of a virtuous woman. These intricate designs were executed with precision, employing the Mother-of-pearl inlay technique. The top and bottom compartments of the swing door were adorned with twisted Ajamun (亞字文) and turtle gate designs.

Handles were installed on both side of each box for convenient transportation. This ‘Nong’ was elevated to prevent damage from the heated floor, and foot-shaped legs were securely fastened to the footrest. Only the corners of the front were reinforced with elixir-shaped plate decorations.”

Collection: Busan Metropolitan City Museum.

H. 116cm, W. 82cm, D. 40,5cm.

The craft of najeonchilgi refers to lacquerware inlaid with nacre (mother-of-pearl), including such items as furniture and accessories.

The surface of the lacquerware is with decorative patterns made by inlaying very thin pieces of nacre (processed from iridescent shells, such as abalone).

Tongyeong, which harvests many abalones, is famous for najeon chilgi nacre-inlaid lacquerware.

This two-tiered chest of lacquer inlaid with mother-of-pearl depicts landscape designs and hexagonal flower patterns (龜甲花文).

Here, the inlay technique involves slicing the nacre into thin thread-like strips and stretching them with the tip of a knife before cutting them off and attaching them to the object.

Collection: National maritime museum of Korea, Busan.

H. 117cm, W. 73,4cm, D. 32,7cm.

Collection: National maritime museum of Korea, Busan.

Collection: National maritime museum of Korea, Busan.

H. 24cm, Diameter 33cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Mid 20th century.

H. 175,5cm, W. 96,8cm, D. 49,6cm.

This design was popular in the latest years of the Joseon dynasty. Late 19th – Early 20th century.

Mother-of-pearl inlay.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

MOTHER-OF-PEARL FURNITURE PRODUCED DURING THE LATE 20TH CENTURY.

Regarded as a symbol of wealth, chests ornated with mother-of-pearl experienced a surge in popularity in Korea during the 1960s and 1980s. It became a sought-after item, with new brides purchasing it as a wedding gift and housewives acquiring it as a status symbol.

H. 65,5cm, W. 45,5cm, D. 17cm.

Photo courtesy of Bucks County Estate Traders, Inc. USA.

H. 190,5cm, W. 92,2cm, D. 47,3cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum of Korea.

The 1960s in Korea marked a period when the economy, previously stagnant due to the Korean War, underwent revitalization. The social atmosphere was increasingly imbued with a growing desire for material wealth. It was during this era that chests adorned with mother-of-pearl lacquerware, radiantly gleaming in five colors and exclusively associated with high-end craftsmanship, emerged as a symbol of affluence and gained immense popularity. Mother-of-pearl wardrobes found their way into countless households, and it became a nationwide trend to possess a complete set of mother-of-pearl doorcases, dressers, and cabinets. Newlyweds often included a set of mother-of-pearl wardrobes in their wedding items.

The primary production center for this furniture was Tongyeong, renowned for its long-standing tradition of crafting the highest quality mother-of-pearl lacquerware. In close proximity, a mother-of-pearl workshop was situated just three or four doors away, and the exquisite mother-of-pearl products swiftly set the standard for furniture nationwide. As the popularity of mother-of-pearl lacquerware grew, the number of factories adopting machine-based abalone shell processing also increased, finding success not only in Tongyeong but also in the neighboring Goseong. During the 1970s and 1980s, the expansion of mother-of-pearl workshops extended to cities like Seoul, Busan, and Daegu, leading to a surge in the number of factories, which is estimated to have reached around 1,000.

The mother-of-pearl lacquerware craze that swept the country persisted until the 1980s but waned in the 1990s. To meet the escalating demand for increased production, synthetic lacquers like cashew lacquer, which are cost-effective and dry quickly, were employed in place of traditional lacquer. However, in contrast to the subtle scent of natural lacquer, synthetic lacquer emitted an unpleasant odor, tended to become cloudy over time, and exhibited lower durability, causing the mother-of-pearl inlay to detach easily. Consequently, consumers gradually began to shift away from it. Furthermore, as residential spaces evolved to accommodate Western-style living, such as Western-style houses and apartments, mother-of-pearl furniture was gradually displaced by Western luxury furniture brands.

Vintage Korean Mother of Pearl Black Lacquer Armoire.

Micro abrasions in lacquered finish, as well some areas with chips in the finish. There is some damage to the right corner of the crown. There is no key for the locks, with the lock on the bottom doors in locked position. Lock on upper doors doesn’t work properly.

49.5 x 27.5 x 80.5 in

Estimate: $500-$3,000

Starting Price: $50

MOVING MISS DAISY LLC (DBA-MISS DAISY’S CONSIGNMENT & AUCTION HOUSE). SANTA BARBARA, CA, UNITED STATES.

June 17, 2024.

LINKS:

Shell and Resin: Korean Mother-of-Pearl and Lacquer.

Fabulous article !