TONGGAGBAN – 통각반: Round tray-tables.

Tonggagban also called Jegi 제기 (祭器) refers to a variety of vessels and tools used in ancestral rites. These items can be made from various materials, including wood, porcelain, and brass. In shrines, ceremonial vessels made of porcelain or brass were mainly used. Wooden jegi were commonly used in graveyards due to their lightweight nature, which made them easy to carry.

Since ancestral rite vessels were dedicated to ancestors, they were treated with great care and not used in daily life. After the ceremony, they were cleaned thoroughly and stored in the ancestral rites storage (祭器庫) of the ancestral shrine or in a specially made wooden box. Additionally, they were neither sold nor lent to others. When the vessels could no longer be used, they were buried in the ground and not repurposed for any other use.

In the late Joseon Dynasty, wooden jegi began to be used at home as well, as noted in the writings of Song Si-yeol.

Namwon, located in Jeollabuk-do, is renowned in Korea for producing high-quality wooden jegi. Drawing on the abundant wood that grew naturally at the foot of Mt. Jiri, combined with the craftsmen’s exquisite woodworking skills and lacquering techniques, the region became the center of Korea’s finest wooden ceremonial vessel industry.

Namwon jegi is lacquered, giving it a vibrant color and exceptional durability. Its lacquer coating prevents discoloration even after prolonged use, earning it a reputation as the finest quality jegi in the country.

Jegi were also produced in the mountainous areas of Gangwon-do. The top plate is circular, and the legs are shaped like barrels, tapering narrower towards the top.

H. 11,7cm, Diameter: 41,2cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 7cm, Diameter: 37,5cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 10,8cm, Diameter: 41,3cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 12,7cm, Diameter: 40,9cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 9,5cm, Diameter: 32,7cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 6,9cm, Diameter: 34,3cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 13,9cm, Diameter: 43,8cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 12,7cm, Diameter: 43,2cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 23,5cm, Diameter: 42,8cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

H. 13,9cm, Diameter: 43,8cm.

Collection: Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, USA.

Mouth diameter: 15,5cm, Bottom diameter: 12cm, Height: 7,5cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Link: Joseon ritual ceramics spotlighted in Seoul exhibition

TTEOKSAL – 떡살 : Wooden molds for rice cakes.

𝑻𝒕𝒆𝒐𝒌𝒔𝒂𝒍, or rice cake mold stamps to form decorative shapes and patterns, was used as early as the 16th century and remained popular during the 19th and 20th centuries.

The stamps can be classified by shape and material, with those with circles and flower patterns usually made from ceramics and those of square or rectangular shapes crafted in wood.

In addition to their decorative function, the patterns pressed onto rice cakes usually convey auspicious messages, such as those “𝒄𝒉𝒖𝒌” (blessing) or “𝒅𝒆𝒖𝒌” (benefit or gain) as shown in the photos

Set of 4 pieces.. Gingko wood.

Early 20th century.

H. 9cm & 6cm. Private collection.

The most common patterns for rice cakes were plants and flowers, such as Chrysanthemums, lotus flowers, plum blossoms, pear blossoms, orchids, pine trees, peony flowers and grape vines. These patterns varies according to which plants and flowers were in season. Korean have always been inspired by the changing seasons. and transformed them into motifs for rice cakes, displaying their artistic skills and deep regard for nature.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

A board that presses rice cakes to create patterns.

It is a rice cake in the form of a seal with a chrysanthemum pattern.

The plate was carved into a mushroom shape to separate the handle and frame.

The frame is circular with a flat bottom and has several chrysanthemum leaves swirling around a central swirl pattern.

The diameter of the rice cake is 8cm, and the diameter of the handle is 5.5cm.

A board that presses rice cakes to create patterns.

It is a seal-shaped rice cake with a cross (+) symbol on it.

The plate was carved into a mushroom shape to separate the handle and frame.

The frame is circular with a flat bottom, and a cross pattern made of seven lines is engraved around the circular flower pattern in the center.

The diameter of the rice cake is 8cm, and the diameter of the handle is 5cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

WOODEN CONTAINERS.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: Gyeonggi Provincial Museum

Collection: Gyeonggi Provincial Museum.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Folk Museum of Korea.

TOOLS

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum.

Collection: National Folk Museum.

VARIOUS ACCESSORIES.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

The overall shape is cylindrical, and both ends are closed using a single piece of bamboo.

The top is in the form of a lid that can be opened and closed.

The body is embossed with a seven-character verse and engraved on the top and bottom. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

A ceremonial object used in place of wild geese during traditional weddings.

Wild goose shape. Wings and tail are engraved on both sides. Collection: National Folk Museum of Korea.

H. 22,5cm, W. 45cm, D. 16cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

A container for storing brushes.

It is a shape made by attaching two bamboo tubes side by side.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

A shape in which 13 barrels of different sizes and heights are arranged regularly around a long central cylinder. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

A container for storing rolled paper.

An octagonal container made by attaching several layers of paper.

On the 8th side, there is a plum blossom and bamboo design. Collection National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: Gyeonggi Provincial Museum

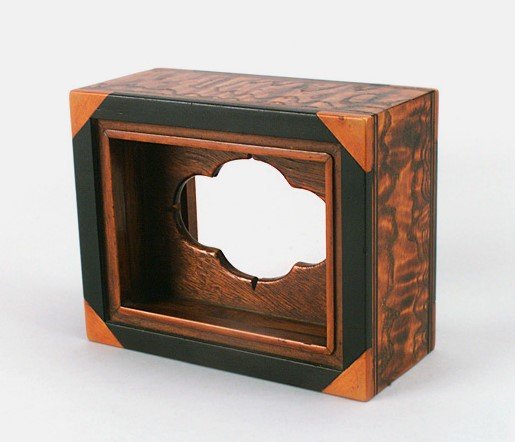

A box for storing inkstones.

It is a turtle-shaped inkstone house with a lid.

The body is carved in the shape of a turtle

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.