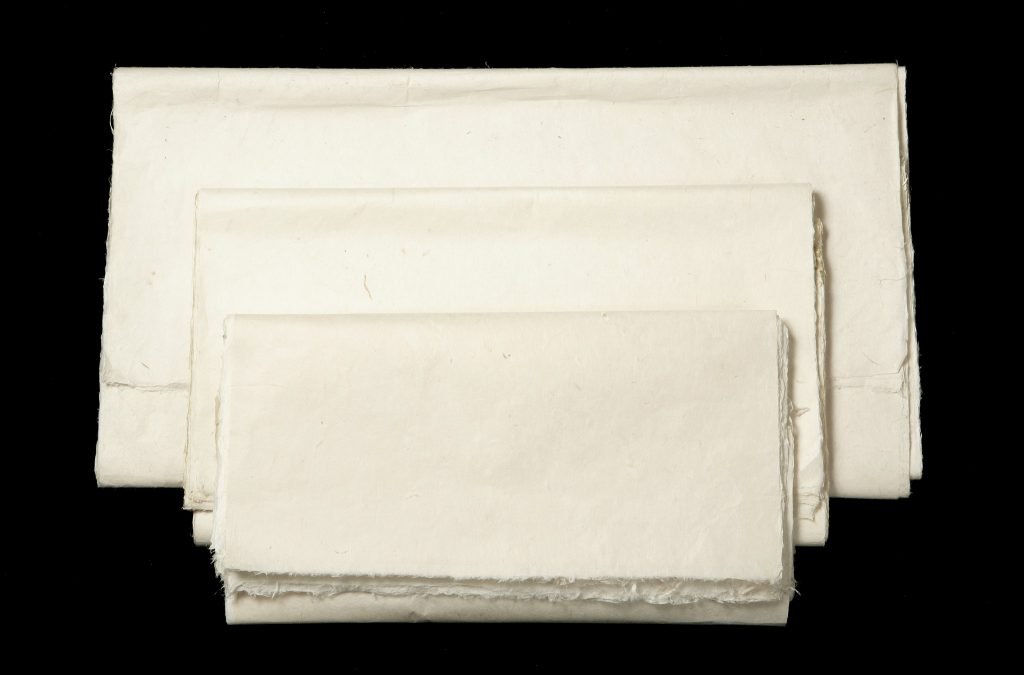

Hanji (Korean: 한지/韓紙) is the traditional handmade paper from Korea. It is made from the inner bark of the mulberry tree or Hibiscus Namihot (also known by its current scientific name, Abelmoschus manihot) both native to Korea, which helps suspend the individual fibers in water.

Despite being paper, Hanji is extremely tough, waterproof, and versatile. Because of its durability and availability, this paper is also used to cover floors, walls, ceilings, windows, doors, and furniture in traditional Korean houses.

Hanji is waterproofed with bean oil and polished.

On furniture, paper was traditionally used to line the inside of Korean chests during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897). These chests were typically used to store clothes, bedding, and other precious items.

It helped protect the stored items from moisture, insects, and mold, and also added a layer of insulation.

On old, unrestored chests, book pages and sheets of newspaper were commonly used. Sometimes, dates could provide clues about the age of the piece.

On reproduction and more recent chests, printed wrapping paper was predominant.

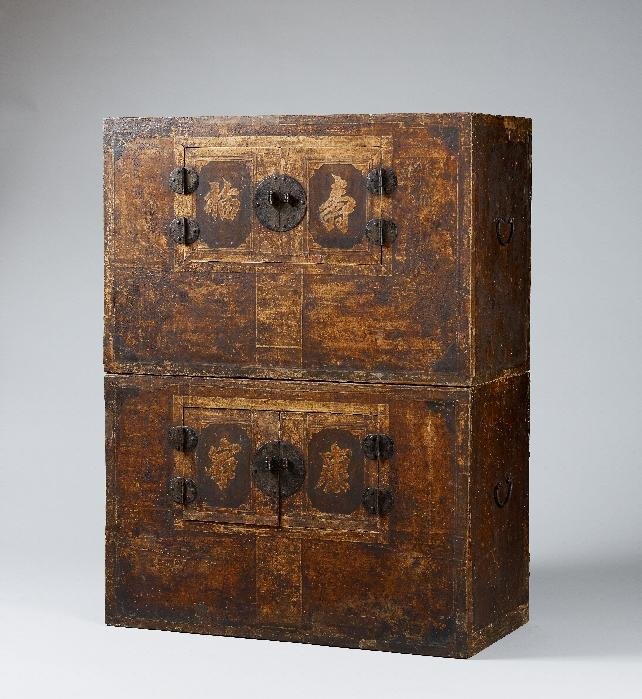

During the Joseon Dynasty, some cabinets were constructed with wooden frames covered with paper. Ordinary wood, such as pine, was typically used for the frame, as the wood’s texture was not visible from the outside.

The quality of mulberry paper, made by boiling mulberry tree fibers and stretching them, was excellent. In the case of paper cabinets, layers of used paper were pasted together, covered with a white sheet, and then finished with the application of vegetable oil.

These types of paper cabinets were primarily used by ordinary citizens who could not afford expensive furniture. Due to the relatively low durability of paper cabinets, worn-out or broken ones were often repaired for continued use. These chests and boxes were used for storing clothes, books, and other small items, often stacked on top of one another. Paper chests were mainly used by women for storing clothes, and colored papers were often applied for decoration.

Today, original pieces in their original condition are scarce on the market because they were less durable against wear and tear and proved challenging to maintain.

This unique furniture-making technique is specific to Korea and is not commonly found in China or Japan.

PAPER-COVERED CHESTS.

Paper cabinets were built or framed with wood and covered with paper. Wooden frames were either constructed specifically for making paper cabinets or used to refurbish worn-out or damaged cabinets by covering them with paper. For the former purpose, a simple wooden frame was made to be covered with paper, and ordinary wood was used since the wooden texture was not visible from the outside. For the latter purpose, the basic frame was made of thin wooden planks, which were then covered with paper.

In the case of paper cabinets, used paper was pasted in several layers, covered with a white sheet, and finished with an application of vegetable oil. These types of paper cabinets were commonly used by ordinary citizens who could not afford expensive furniture. Due to their low durability, worn-out or broken paper cabinets were often repaired for continued use.

Cut paper on wood, iron fittings. Gyeonggi province, Korea.

Mid 19th century.

H. 82cm, W. 88cm, D. 48cm. Collection “ANTIKASIA“

H. 37,3 cm, W. 52,5 cm, D. 26,1 cm. Pan Asia collection.

Reference: Korean wooden Furniture (Park Young-gyu, Samsung Publishing House, 1982)

Iron fittings.

H. 41,7cm, W. 52,5 cm, D. 26 cm. Pan Asia collection.

Reference: Korean wooden furniture (Park Young-gyu, Samsung Publishing House, 1982)

Colored paper, lacquer finish, pine wood, wire, tin fittings

H. 60cm, W. 76cm, D. 32,4cm.

DATE circa 1900. Collection of the Albert Weisman Art Museum Collection, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Colored paper on pine wood, iron fittings

H. 86,4cm, W. 52cm, D. 26cm. DATE after 1910.

Collection The Albert Weisman Museum of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Oiled paper, pine, iron fittings

H. 85cm, W. 70cm, D. 37cm. DATE circa 1900.

Collection The Albert Weisman Museum of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Multipurpose furniture for storing items such as clothes, books, or dishes.

It is a wood-framed Jizo (木骨紙欌) with a rectangular frame made of wood and paper applied to the outside. The door plate is connected by a spool-shaped hinge with a swastika embossed on it, and a ‘ㄷ’-shaped lock is inserted into the spool-shaped front base. Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul, Korea.

Traditional paper was glue to the wooden frame. Few of those chests remained in original condition as the paper was very fragile. This chests were mainly used to store papers and documents.

Early 20th century.

Collection National Folk Museum of Korea.

Collection: Gimhae Folk Museum, Korea.

H. 83cm, W. 81,5cm, D. 42,5cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul, Korea.

Collection National Museum of Korea, Seoul.

Covered with paper. Iron fittings.

H. 91,6cm, W. 66,5cm, D.33,5cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul, Korea. (3 photos).

H. 87cm, W. 66cm, D. 31cm.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

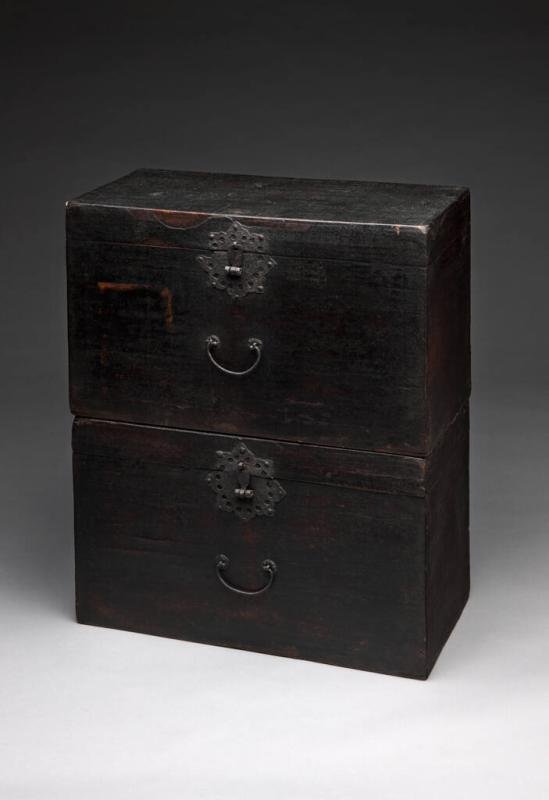

PAPER BOXES.

Beside furniture traditional Korean paper was widely used for the confection of smaller boxes used to store various accessories.

To make paper boxes, several layers of bush clover, bamboo, willow, plain wood planks, or paper were thickly pasted together and then covered with paper. These boxes were used for storing clothes, books, or other small items, and they were often stacked on top of one another. Paper boxes were mainly used by women for keeping clothes, and colored paper was often pasted on them for decoration.

Paper covered box, clear lacquer finish, and yellow brass fittings.

H. 21cm, W. 47 cm, D. 24cm

Late 19th Century.

Gyeonggi province, Korea. Collection “ANTIKASIA“

H. 22 cm, W. 66 cm, D. 32 cm. Pan Asia Collection.

After covering the wooden box with a first layer of paper, arabesque patterns were cut with colored paper.

Paper over wood, brass fittings

H. 44,4cm, W. 73,6cm, D. 39,3cm. DATE 1800s.

Collection The Weisman Museum of Art, Minnesota, USA,

Wood, paper, and iron with an oil finish, 8 1/4 x 17 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. (20.96 x 44.45 x 21.59 cm), Gift of Frank S. Bayley III, 92.157 Collection of the Seattle Museum of Art, USA.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Folk Museum, Seoul.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

Collection: National Museum of Korea.

H. 6.5 cm, W. 16 cm, D. 16 cm – H. 7 cm, W. 16 cm, D. 16 cm – H. 5 cm, W. 12,5 cm, D. 12,5 cm. Pan Asia Collection. For these boxes, several layers of paper were glued together. A technique similar to papier mache .

Reference: Paper craft culture

(Lim Young-ju, Sang-ho Lee, Daewonsa, 1999), Life and culture of Joseon women (Seoul Museum of History, 2002)

H. 20,5 cm, Lid diameter: 35 cm,

Bottom diameter. 19.2 cm.

Chuncheon National Museum collection.

To reinforce the structure, perilla oil was also applied to the surface.

H. 5cm. W. 19,7cm, D. 15 cm. Reference: Paper craft culture

(Lim Young-ju, Sang-ho Lee, Daewonsa, 1999), Life and culture of Joseon women (Seoul Museum of History, 2002)

Pan Asia collection. These boxes were used to store letters and documents. A wooden frame was first built and used as a base to attach several layers of paper inside and out, or simply apply multiple layers of paper to make a thick box. Oil was then applied to the surface.

In addition, the surface was decorated with colored pieces of paper.

H. 18cm, Diameter 36cm. Pan Asia collection.

References: Korean costumes Jooseon Seok, Jinjae Bo,1978.

In this “Gatjip” or hat box the base (the part on which the hat is placed) and the cover are not separated, and it is usually made by making a skeleton in a cylindrical shape with the lower part and a conical shape on the upper part. Paper is then applied and oiled.

OTHER KOREAN ITEMS MADE OUT OF TRADITIONAL PAPER

Size Stem length: 16cm, Width: 22,5cm,

Total length: 33,5cm. Pan Asia collection.

After attaching paper to the fan, the upper part was painted red only on the 1/4 part. Colored paper with the “Taegeuk” pattern was cut in the center. The periphery was framed with black paper and greased. The handle was fixed with two metal nails, and painted black.

H. 120cm, L. 65cm, D. 40cm.

Oak wood, paulownia wood, hanji paper, iron fittings.

Carpenter: Hong Hoon-Pyo.

The three-story hanjijang of Somokjang Hong Hoon-pyo continues this tradition of the Joseon Dynasty.

Collection: Sookmyung University, Seoul, Korea.

Paper over wood, wrought iron fittings, natural lacquer

H. 36,8cm, W. 62cm, D. 30,5cm., DATE circa 1900.

Collection: The Weisman Art Museum, Minnesota, USA

APPENDIX:

Hanjijang (Korean Paper Making/한지장 韓紙匠)

Hanjijang refers to a craftsman skilled in the art of making traditional paper, hanji, from the bark of mulberry (Broussonetia kazinoki) trees and mulberry paste. Making hanji requires great skill and extensive experience. The process involves collecting mulberry bark, steaming, boiling, drying, peeling, boiling again, beating, mixing, straining, and drying. It is said that 99 processes are required to produce this paper, which is why the final process is also called baekji, meaning “one hundred paper.” During the Goryeo Dynasty, Korean hanji was so renowned that the Chinese referred to the best-quality paper as Goryeoji, literally meaning “Goryeo Paper.” Sun Mu, from the Song Dynasty of China, praised Goryeo paper in his book “Jilin leishi” (Things on Korea), describing it as white, glossy, and lovely.

In the Joseon Dynasty, starting from the time of King Taejong, the state began to oversee paper production by establishing the office called Jojiseo (Paper Manufactory). However, in modern times, changes in architectural styles and housing environments, as well as the import of paper, have led to the virtual disappearance of traditional hanji. Today, due to high production costs, hanji is made using pulp imported from Southeast Asia rather than mulberry bark. To preserve the art of hanji and pass it on to the next generation, the Cultural Heritage Administration has designated hanji making as an Important Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Following illustrations: Paper making process.

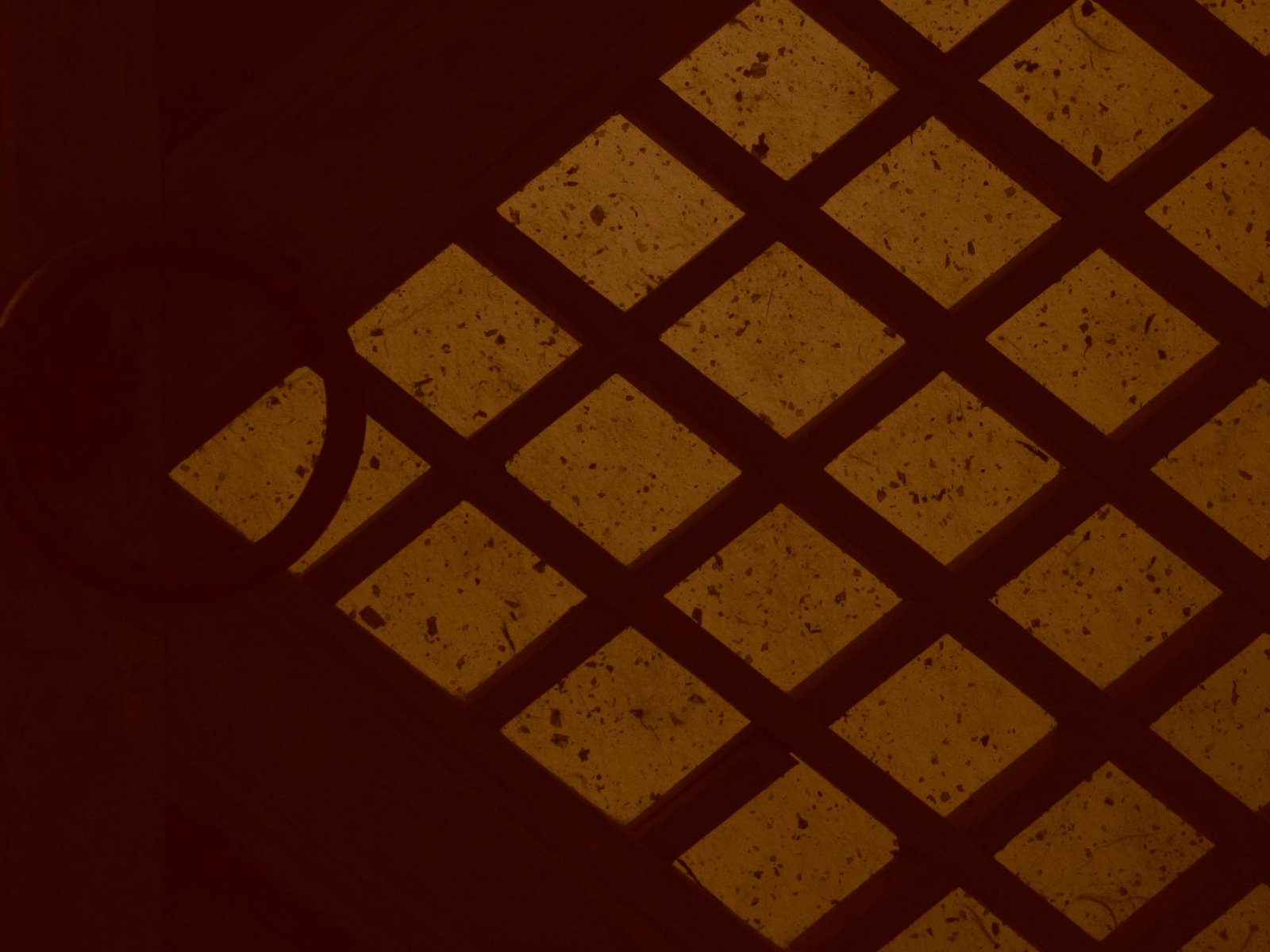

Lining the inside of a Korean antique chest.

Lining the inside of a Korean antique chest with sheets of paper is a delicate process that preserves the chest’s interior while adding a traditional touch. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to line it properly:

Materials:

Hanji paper (mulberry paper). Some mulberry paper can be found on Amazon.

Soft brush (for applying glue)

Rice glue or starch paste (traditional adhesive). Any water-based glue can also be used, Select a transparent glue.

Instructions:

Prepare the surface:

Clean the inside of the chest with a dry cloth to remove any dust or debris.

Cut the paper:

Lay the hanji paper on a clean, flat surface. Using the measurements, cut pieces of hanji to fit each section of the chest. Add a small margin (about 1 cm) if you’d like the edges to overlap slightly for a seamless finish.

Prepare the glue:

You can use readily available water-based glue. Ensure the glue is slightly diluted with water (ratio: 2/3 glue, 1/3 water) so it spreads evenly.

Apply the glue:

Use a soft brush to apply the glue evenly to the surface of the chest. Work in small sections to prevent the glue from drying too quickly.

Attach the hanji paper:

Carefully place the cut pieces of hanji onto the glued surface, starting from one edge and gently pressing it down with your fingers.

Smooth out any bubbles or wrinkles with a soft, damp cloth or your brush, working from the center outwards. You can even apply more glue on top of the paper to eliminate wrinkles and bubbles.

Drying:

Allow the hanji to dry naturally in a well-ventilated area. Avoid direct sunlight, as it might cause the paper to shrink or discolor.

Final Inspection:

Once the hanji is dry, inspect for any loose edges or bubbles. Smooth these out using additional glue and gently press them down.