About twenty years ago, a close friend gave me a book that he had found at the Bouquinistes of Paris (booksellers of Paris) along the banks of the River Seine.

“Vive la chine”, memoires d’un antiquaire by Jacques Helft was published in 1955. This book has been translated to English as Treasure hunt, Memoirs of an antique dealer.

Jacques Helft lived at the beginning of the 20th century and hailed from a prestigious family of antique dealers in Paris, spanning two generations.

In the opening of his book, Jacques Helft describes his apprenticeship as an antique dealer under the tutelage of his father and grandfather, a period that transpired at the end of the 19th century. During this era, it was commonplace for dealers to scour attics and sheds in search of concealed treasures. A common practice was to purchase lots with the hope of uncovering valuable pieces within.

Over time, the market began to dwindle, prompting Helft to explore new territories. To achieve this, he ventured eastward to Russia and the Slavic countries, where numerous valuable pieces were still available at affordable prices. He subsequently sold these items in Paris or the United States, where the demand was significant.

As for Asian art in general, a substantial portion of the valuable pieces now exhibited in museums worldwide or held in private collections were acquired during historical expeditions, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Explorers and dealers embarked on journeys to the source, the countries of origin, with the intention of procuring treasures at a reasonable cost or, in some cases, appropriating items left behind by local populations.

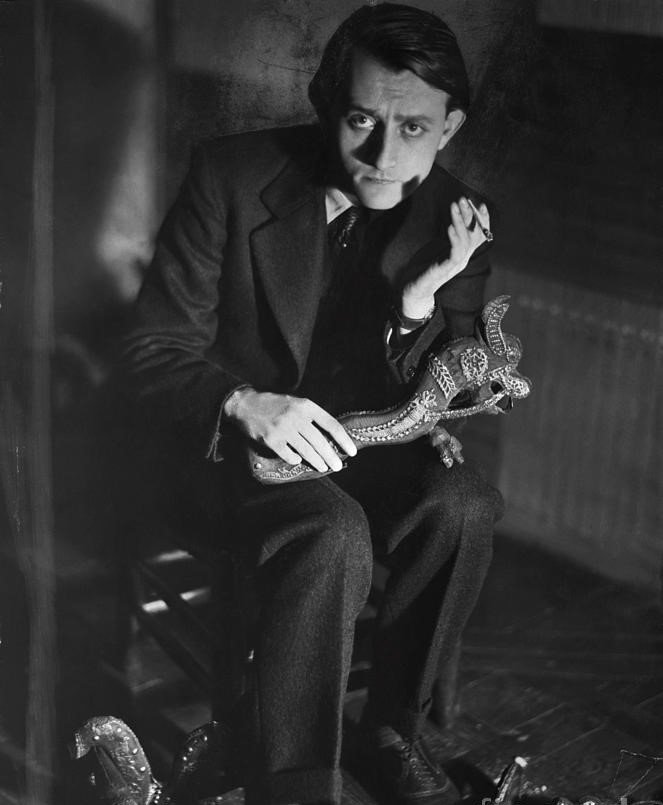

In this regard, the story of Malraux in Cambodia, who later became a minister of General de Gaulle, is a perfect illustration. It was 1923 when Malraux, then 22, arrived in Cambodia with his wife Clara. Newly broke Parisian intellectuals, they had a scheme to steal statues from the Angkor temples to sell in the West. He describes his trip in his book “La voie Royale” first published in 1930.

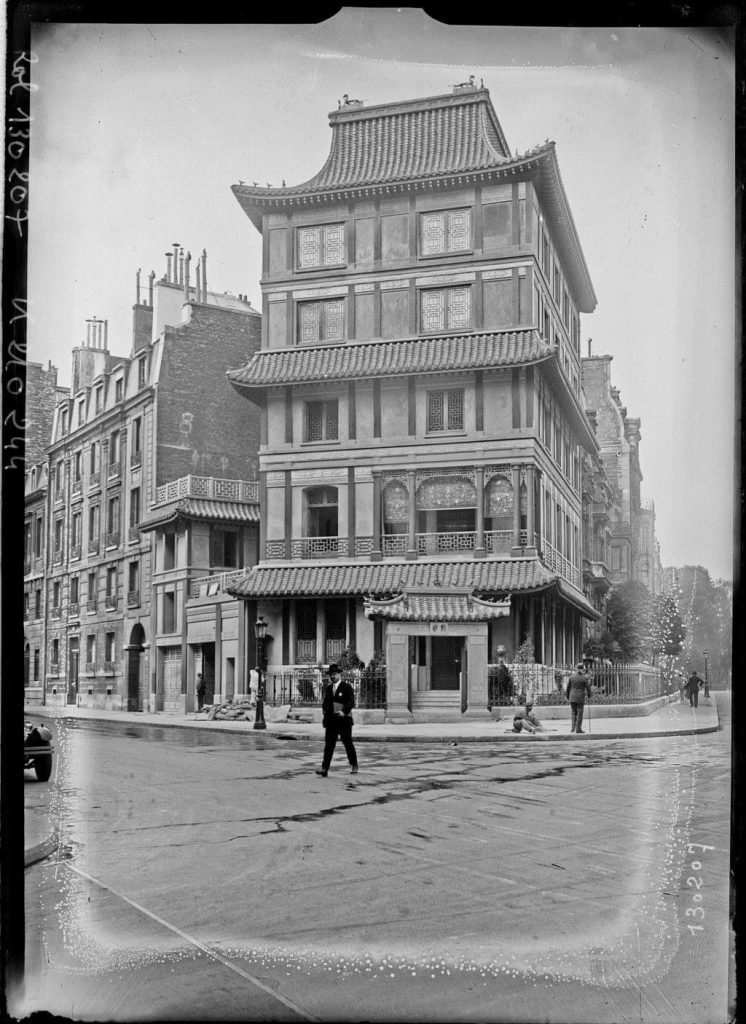

Another good story concern the life of CT Loo

Loo was 15 when he started working as a cook for the wealthy family of diplomat Zhang Jinjiang in Huzhou, Zhejiang province. Seven years later, in 1902, Zhang was posted to France and Loo accompanied him. When the diplomat opened a shop selling Chinese porcelain, carpets, lacquer and silk in Paris, Loo became a sales assistant. In 1908, he set up his own gallery in the French capital.

This was a time when the West was fascinated with chinoiserie and collectors were looking for 18th- and 19th-century porcelain. Loo dealt in those pieces to begin with because they fetched high prices. He began by sourcing items from other dealers in Europe but, within a few years, he’d set up offices in Beijing and Shanghai. And he soon began exporting much bigger, better quality objects: huge sculptures and frescoes. This was a new market and Loo’s success was in educating European and American collectors about what they were buying.

Until the 80s (20th century), It was still possible to acquire some interesting pieces in countries that were beginning to open their borders to foreign visitors. In Asia, this was the case in particular in China and the countries of Indochina. (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos).

During the second part of the 20th century, came the boom and the fashion of Asian furniture in Europe and the United States. Entire containers were exported, and warehouses in China were the size of soccer stadiums. You could still find some good pieces but most of them were restored and rather destined to a decoration market. Then slowly the market declined. Towards the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, the demand for Asian furniture gradually decreased.

Today, a significant number of antique dealers have ceased their operations. From my perspective, I’ve observed that in Thailand and Taiwan, approximately 60% of the galleries have shuttered in the past five years.